In 1994, Ross Thompson invited us to join him on one of his insulator hunts

tracing the 1870's telegraph lines set up by the U.S. Army to connect the

western forts from San Diego, California through Arizona's Forts Grant and Bowie

to New Mexico's Fort Union. The job of the military was to keep the Apaches at

bay, and communication was a key element. After a few hunts, Ross passed along

the search for the "holy grail" to Steve Kelly and Tom and the hunts

continued with a changing cast of characters involved. There were many trips

into the land of saguaro cactus.

One of the first explorations ended with the whole group being trapped by a

flash flood and marooned on islands separated by the rising water for more than

twenty-four hours, but everyone survived and my great finds included a beautiful

tiny birdpoint arrowhead and hundreds of needle like quartz crystals - but no

insulators. In fact most trips into this area resulted in a greater picture of

the history that took place here, experiences of a lifetime with tarantulas,

bird sightings and wonderful camaraderie with a fine group of people in the

insulator hobby. But insulators were few.

However on one Arizona trip, Rick Bentley, and Tom and I had established that

the old military road might not have followed the present road, because for a

stretch of about a mile, we found no trace of the old line: no wire, no pole

stubs, no glass pieces. The following day we investigated off to the side,

finally finding the indentation of the old original military road that had been

laboriously constructed 125 years ago to maintain the telegraph lines and to

haul supplies to the forts. On closer inspection, we began finding pieces of the

wire, piles of rock that had been used to support the poles and we even found

glass! Rick and Tom each found "blobs" (CD 126) in beautiful yellow-green and yellow-olive amber. I found a yellow-green "blob,"

broken, but held together by its tie-wire, hanging upside down. I'm sure that

over the years, it collected water in the pinhole when it rained and snowed.

Freezing temperatures and expanding ice most likely broke this beautiful piece.

The next day we found the next section of the old military road that climbed

to the pass on the Natanes Plateau. Here we found several chips of E.C.&M.'s

that were the original insulators used on that line. (About 1878-79, the CD126's were used as replacement glass). In an

area where several chips were

scattered on the hillside, I saw the outline of a beautiful aqua with olive /

amber streaks and bubbles, half buried in the dirt. I remember thinking,

"This can't possibly be whole" as I carefully dug the dirt away - and

it wasn't. A large piece was missing from the back. But what a thrill! These

pieces tell a story I'll never forget.

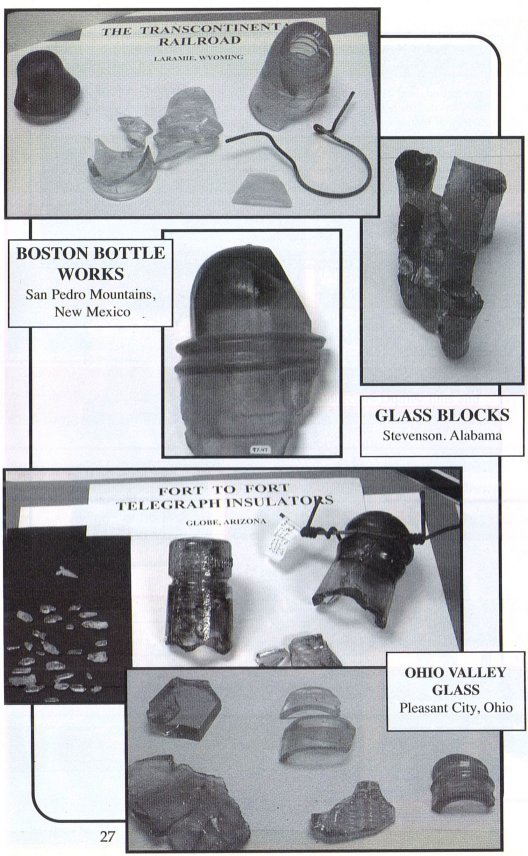

GLASS BLOCKS

STEVENSON, ALABAMA

This was supposed to be a business trip. In July 1991, Tom had some work to

do and meetings to attend in Huntsville, Alabama, but he suggested that at the

end of the week, I should fly down to join him for little R & R. In a rented

car, we took off to explore Alabama with our trusty AAA travel book in hand.

Stevenson was listed in the travel guide for its old Railroad Depot Museum,

"with displays of photographs, memorabilia, and Civil War artifacts. During

the Civil War, this railroad junction and its depot were strategically vital to

the South." We like such historic spots, especially those connected to

"trains" so after driving for a couple of hours through beautiful

countryside, Stevenson was the next stop.

Much to our disappointment, the museum was closed.

The old red brick depot/museum sat like an island in the middle of multiple sets

of railroad tracks. It was still very early in the morning and we were hoping

that it might open later, so we peeked in windows to see if it were worth

returning to see. We made our way around each side, looking in where we could.

But walking around the depot, we each spotted pieces of aqua colored glass we

had kicked up in the gravely surface that frequently covers the ground in

railroad areas. It was definitely thick aqua glass, as found in insulators, not

bottles. But unlike the insulators I usually see, there was nothing that looked

like round sides or domes or skirts, no parts of a threaded pinhole and no

embossing. Instead it had straight edges! What it looked like was a piece of a

glass block insulator! (CD1000)

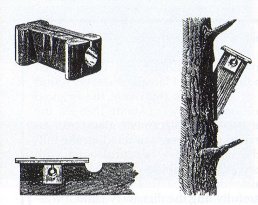

During the early years of telegraph line construction, the glass block was a

popular form of insulator. They could be placed either in a crossarm, notched

for the block to be dropped into place, or in a side bracket shaped to receive

the insulator. They were widely used in the late 1840's on a telegraph line running between Washington D.C. and New Orleans.

Could it be that we had found a piece of history almost 150 years old, one

that had seen the Confederate soldiers traveling by train through this site and

the eventual occupation by Union forces? Were there more Pieces

here? When we scratched through the stony surface, we found more pieces... and as I manipulated the

pieces in my hand, I could see how some of the chips fit neatly together.

Several shards could be pieced together into one glass block! Not all the parts

could be found, but what stories this piece could tell.

BOSTON BOTTLE WORKS INSULATORS

SAN PEDRO MOUNTAINS, NEW MEXICO

Our bottle collector friend, Jerry Simmons, invited us to go with him to an

area east of Albuquerque to look for remnants of old communication lines to some

of the mines in the region. He had seen pieces of glass shards in this area that

he thought might be unusual insulators. On an April day in 1997, a group of

searchers headed out with Jerry who had obtained permission from the private

landowners. It was a beautiful New Mexico spring day as we headed up the hill into

the San Pedro Mountains.

Jerry showed us the area where he thought the lines must have traversed and

we spread out looking for some evidence of the old line. Eventually we made a

find, glass shards spread out over 20 square feet. Most pieces were too small to

be recognizable, but the unique pinhole threads on one shard were the clue that

this was a Boston Bottle Works insulator!! A very unusual find in New Mexico!

The identification I.D. was the pinhole threads that were divided into 4

vertical segments. This was an innovation patented by Boston Bottle Works'

Samuel Oakman, October 15, 1872, as a improvement over the threadless insulators

used until that time. These insulators were six-sided on the outside and could

be threaded unto a wooden pin with a special wrench-like tool. Later a friend

found a larger piece of another insulator found near this area, and on this one,

you could see "FOR" lightly embossed on the base of the inner skirt.

The history of this company indicates that this is part of the "BOSTON

BOTTLE WORKS PATENT APPLIED FOR - " embossing and that these insulators

were produced in 1871 or early 1872.

(illustrations from McDougald's "A History and Guide to North American

Glass Pintype Insulators", p 3, and 34)

San Pedro New Placer Mine District may have ordered these "newfangled

modern" insulators when installing communication lines during the early

1870's; or perhaps they may have installed "used insulators" from the

dismantled Fort to Fort telegraph lines that had run further north through Fort

Union around the turn of the century. The latter is more likely because a

variety of insulator types were found in our search.

We also found a dump from the mine where our bottle collectors in our group

found some interesting pieces from the turn of the century. And we found some

very nice pyrite and garnet crystals on "Garnet Ridge," nearby. There

is still much to learn and the hope of finding more "STORYTELLERS"!