A Closer Look - Part 3

TYPE OF GLASS AND LOCATION OF MANUFACTURE

AS RELATED TO AGE

It is doubtful if any of the PETTICOAT beehives were made at Muncie. There

are very few of these made in the color of glass used at Muncie, and there are

no signs of Muncie presses or engraving. (For one possible exception, see data

under the "STRAIGHT-SIDES" heading later on in this article.)

Another

point; in 1911 the CD 152 replaced the CD 145 as the standard for both Western

Union and Bell. All CD 152s except for the very latest (which have the

later-style embossing) have machined letters. Probably about 1895 production was

started at Muncie on the H. G. CO. CD 145 in Hemingray blue; and these were the

Western Union standard used for about 15 years, or until the CD 152 was adopted.

After that, Hemingray offered the CD 145 embossed "HEMINGRAY" with or

without drips.

There's no real proof, but it seems hard to believe that the H.

G. CO. PETTICOAT insulator continued to be made at Covington for a long period

of time simultaneously with the Muncie H. G. CO. that was standard to 1911 when

the CD 152 came in. The later Muncie production is of so much higher quality

that there would have been no real reason for maintaining production of both

(and it seems doubtful that any items so crude and colorful would have been in

production as late as that. More on quality and uniformity of color later on.)

Also, they were probably discontinued when Muncie tooled up to make trainloads

of those plain H. G. CO. pieces for Western Union, probably in the mid-1890s.

So, "our" beehives were probably primarily made during the ten-year

period from 1885 to 1895, give or take a year either way, making their years of

production about 12 years at the most. However, the molds were kept and were

used as required, perhaps sometimes after a period of nonuse.

QUALITY

Having touched on quality in the previous paragraph, it might be of interest

to give more details here. The quality and appearance of most of

"our" beehives is that of "older" glass. Many units contain

large bubbles, small rocks, bread-like impurities, and straw marks. In the early

years of glass manufacturing, these things were more common than they were

later on in glass-making history. The atmosphere in most of the plants was uncomfortable; the air was hot, and filled with smoke, dust, steam, toxic

gasses, and noise. Fires were common as were injuries to the workers. While even

today glass shops are not the most comfortable of places to work, Hemingray had

a reputation in its time for quality products. In the late 1800s, the making of

insulators certainly didn't demand the controls required of bottles, jars,

lamps, and so forth. But "our" beehives were good enough that the

purchasers were more than pleased. In spite of the times in which they were

made, these beehives are of excellent quality. As time went on and conditions

and methods improved, so did the quality of the glass.

Although glass

manufacturers usually strived for good-quality products, purchasers, especially

later on, would issue specifications and drawings with measurements for

insulators to glasshouses. And, over time, they would tighten up those specs.

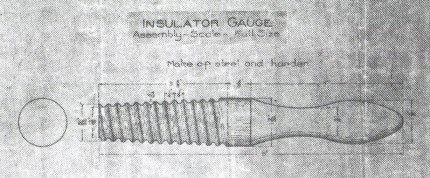

Purchasers would also make inspections using gauges. Here's a quote from a spec

from Western Electric dated May 24, 1907: "The quality of the materials

used and the methods of manufacture, handling and shipment shall be such as to

ensure for the finished insulators the properties and finish called for in these

specifications. The manufacturer must make sure that all material and work is in

accordance with the specifications before the insulators are delivered. The

Western Electric Company is to have the right to make such inspections and tests

as it may desire of the materials and of the insulators at any stage of the manufacture,

such inspections not to include inspection of the

processes of manufacture. The inspector of the Western Electric Company shall

have the power to reject any material or insulator which fails to satisfy the requirements

of these specifications. Inspection shall not, however,

relieve the manufacturer from the obligation of furnishing satisfactory

material and sound, reliable work. Any unfaithful work or failure to satisfy the

requirements of these specifications that may be discovered by the telephone

company on or before the receipt of the finished insulators shall be corrected

immediately upon the requirement of the telephone company,

notwithstanding that it may have been overlooked by the inspector.

"Where maximum and minimum dimensions are shown the dimensions shall be within the limits specified. Where limits are not shown the dimensions shall be

approximate... All material and workmanship unless otherwise specified shall be

of the best grade... The insulators shall have a finish in accordance with

the best commercial practice ensuring, as far as possible, freedom from flaws,

cracks, blow holes, sharp edges and other defects. C. E. Scribner, Chief

Engineer." (These specs were for, standard, pony, and transposition

insulators.)

According to additional information in these specs, size was to

be uniform within each design. There were visual inspections made as well as

actual measurements taken. The threads were checked with a full-sized threaded

steel pin (see Figure 22), and they were to be only so far from the crown of the

insulator, taking at least two complete revolutions to release the insulator

from the gauge, be smooth and of uniform pitch, well-centered within the

insulator, and the gauge could not touch the inner surface of the petticoat.

Every insulator was not checked; ten out of 100, 15 out of 1 ,000, etc. Of the

amount checked, very few could be defective if the whole group was to be

accepted.

Figure 22

Engineering drawing of steel insulator gauge

from Western Electric

December

12, 1904

(Courtesy of Glenn Drummond)

Although these Particular specs applied to insulators made a bit later than "ours", I felt that this

information would be of interest to students of insulator history.

"PETTICOAT"

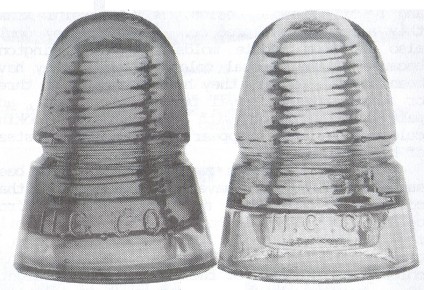

The word "PETTICOAT" is embossed on the back of the skirt on

"our'" beehives. (See Figure 23 ) As stated earlier, the petticoat

idea was patented by Oakman in 1883. Brookfield, Hemingray's competitor, was

the only one to mark their insulators with Oakman's patent date, but then

Brookfield embossed a lot of information on their insulators. Possibly for this

reason, Robert Hemingray purposely stayed away from embossing his insulators in

the same manner. Additionally, Brookfield had made arrangements with Oakman for patent

rights, so that probably wouldn't have been possible for Hemingray.

Figure 23

Back "PETTICOAT" embossing

(Courtesy of Roger Inselman)

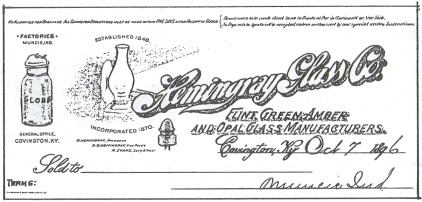

Figure 24

Company invoice-head (restored by author)

October 7, 1896

(Courtesy of N. R.

Woodward)

By styling the

insulator somewhat differently, he hoped to avoid a lawsuit, which it seems he

did. And as already stated, he may have felt he could not be violating any

patents since his insulators had no paraffin recess. However, Hemingray did ask

the advice of a lawyer, whose answers are found in a letter from Cincinnati

dated December 7, 1888: "I have carefully examined the patents on

insulators No. 288,360 [double petticoat]... and No. 14674 ["beehive"

design]... Upon comparing this [first] claim with the insulator submitted to me

and proposed to be manufactured by you, I find this insulator has no [paraffin

recess], which is a prominent and essential element of the claim, and it does

not infringe this claim... The only elements of this [second] claim, that are at

all new, are the shield E [the space between the outer skirt and the petticoat] and the

recess H [threaded pinhole]... in manufacturing the insulators, you would not

infringe the claim...The novel elements of the claim, [namely]: The shield E,

and recess H, are clearly shown in the old insulator manufactured by you... the

only difference being a difference of degree, which is never patentable... I

can therefore unhesitatingly say, that this claim is invalid upon the evidence

now in your possession. I believe other evidence can be produced also, to defeat

the claim...As to the design patent.. . The last form of insulator submitted to

me, is not a paraboloid, the lower part or skirt flares outwardly, making a

reverse curve. It would not therefore infringe the claim of the design patent,

but in addition...it is within my own knowledge and doubtless within your

[sic], that insulators in the shape of a paraboloid, were made and used long

prior to 1884, and while they may not be shown in the records of the Patent

Office, they are certainly very old in public use, and the patent is

unquestionably invalid." Was this request made by Hemingray because of a

threat of litigation, or was he seeking advice just in case. We may never know.

The word "petticoat" didn't "belong" to either Oakman or

Brookfield. It appears to be a Hemingray invention, having been referred to in

others' papers as an "annular recess", which is actually the space

between the outer skirt and the petticoat. There's no reason to believe that

there was ever any conflict over the use of that word. (Had a conflict arisen

over the Oakman patent, it would have concerned the styling of the insulator

rather than what it was called.) We may never know for certain if the use of the

word "petticoat" was tied to agreements with Oakman, since most of

Hemingray' s records (from Covington also) were destroyed in the 1892 fire at

the new Muncie factory. In fact, because of that and other events, many

questions concerning the operation of the company and its products may never be satisfactorily answered.

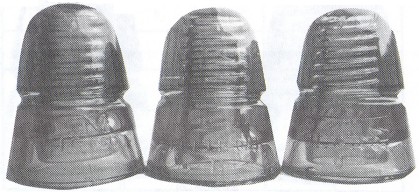

THREE STYLE VARIATIONS

H. G. CO. PETTICOAT beehives have been found so far in three major style

variations; the "tall-dome" style, "straight-sides" (or

"Postal" style), and "normal" style. (See Figure 25) Both

the tall-domes and normals are classified as "flared-skirt" styles. The

color variety and general (older) appearance of the glass in the flared-

skirts is almost positive proof that they were produced at Covington. It is

extremely doubtful if any were made at Muncie, as stated earlier. (More on this

later.)

Figure 25

Three style variations

Left to right: Straight-sides, normal, and tall-dome

styles

(Courtesy of Chris Hedges)

"TALL-DOME" STYLE

The tall-dome style beehives show up once in a while, though not nearly as

often as the normal style. 'They are found mostly in light green with a little

snow, although a few have been seen in green aqua, three are known in jade milk

with pronounced milky swirls, and recently one came to light in blue aqua, full

of snow, with a large bubble and a small olive swirl in front. All have relatively flat crowns compared to the others, and every one

I've had so far came from the same mold (with a hand-engraved "K" in

front), so apparently there was only one mold like that. How did the difference

happen? Perhaps the mold maker deviated slightly from the basic height and

realizing his mistake, flattened the crown somewhat. Although the skirts are the

same vertical size as the normal-skirt style, even with the flattened crown this

style is still noticeably taller from wire groove to crown than the normal

style. 'This was most probably an unintentional variation rather than an

engineering specification.

"STRAIGHT-SIDES" STYLE

The straight-sides are Postal-style beehives. They are of later manufacture

than the others, yet seem to be Covington glass. There are questions, however,

concerning their age and place of manufacture. A few of these have surfaced, but

they are not nearly as common as the other styles. Because of the improved

quality of glass and newer, sleeker design, it is possible that they are a

Muncie product. However, they could also be from Muncie molds used at Covington,

because of the unusual colors in which they have been found. So far, they have

turned up in three or four shades of royal purple, green aqua, and pale green.

Along with the different-looking colors, the letters appear to be machined

instead of hand-engraved.

The royal purples mayor may not have been sun-colored,

but may have been manufactured that color at a later date at Muncie, possibly

from cullet from old purple bottles. Another possibility is that the color came

from glass from a tank being used to make other glassware of that color. The

diameter of the more slender straight-sides beehive (at the base) measures 1/4" less than the flared-skirt variety. The glass is "cleaner", with

few bubbles, snow, straw marks, or impurities sometimes found in the flared-skirts. Also, no straight-sides has yet been seen with skirt or crown

letters.

Were new molds perhaps made up at Muncie so that Hemingray could run

these as replacement insulators? It was an extremely popular style, and as the

lines where the first ones were serving needed replacements, Hemingray could

have been asked to make more after they had been at Muncie for many years. It

is doubtful if they were intended for the Canadian market. No Postal CD 145 was

used in Canada or manufactured by a Canadian firm. And although they are similar

to a CD 143, when Canada did finally go to a double petticoat style, they went

to the big ones like G. N. W. TEL., etc. Of course, at this point it is a

guessing game concerning when, where, and. why they were made, and we will

probably never know the true story.

EMBOSSING DETAlLS

Figure 26

Two more examples of hand-engraved and machined letters

(See also Figure

21)

(Courtesy of Ray Klingensmith)

SKIRT AND CROWN LETTERS

The flared-skirt series (normal and tall-dome styles) are often found with

skirt and crown letters. (See Figures 27 and 28 respectively) (To call them

"petticoat" letters is a misnomer, as they actually appear on the

skirt, even though that is considered the outer petticoat on a double petticoat

insulator.) Of those found so far, these letters go from "A" through

"N", with the possible' exception of "F". (More on "F" later.) No

numbers have yet been found. Sometimes the letter appears on the front of the

skirt, sometimes on the back (see Figure 29), and at times, letters are found

on both skirt and crown. Then again, some pieces have no letters at all. So

far, those found have displayed a pattern; only certain letters appear above

the H. G. CO. embossing, while certain others only appear below. (See Figures 27

and 30) Also, where both back and crown letters exist on the same unit, they

are always the same letter. (Front and crown letters on the same beehive are

extremely rare: I've only heard of two.)

Figure 27

Skirt letters

Left to right: Front (top) "M", back (bottom) "H", front

(bottom)

"J"

(Courtesy of Roger Inselman)

Figure 28

Crown letter "B"

(Courtesy of Roger Inselman)

Figure 29

Skirt letters

Back (bottom) "G" and front (bottom) "J"

(Courtesy of Chris Hedges)

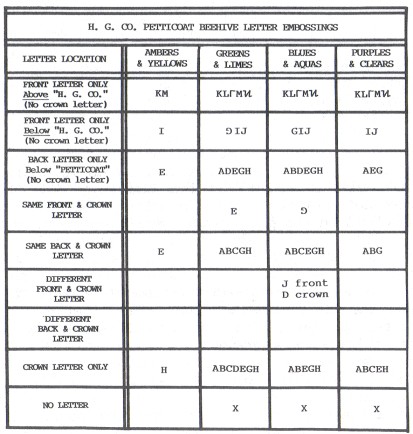

The accompanying chart (Figure 31) will make it easier to see the pattern,

also showing that the letters used are consecutive (not random through the

alphabet).

Figure 30

Showing which letters appear on skirt front and back

Large Image (152 Kb)

Figure 31

These letters served primarily as shop letters. Usually a team of four men

formed a shop in a glassmaking establishment, and each had his own job in the completion

of the steps necessary to produce a glass item. Shop letters (or

numbers) served as a means of determining the output of one shop as the product

emerged from the annealing lehr (slow-cooling oven). Visualize the petticoat

insulators being made simultaneously on several hand presses, each with a single

mold. From the press, the insulators were placed immediately into the huge

lehr. Twenty-four to 36 hours later when they came out at room temperature ready

for the packing process, they were sorted by the shop letters and counted (or

perhaps weighed after packing), in order to deternine pay for the press operator

and his helpers.

It is not likely that these letters were just mold letters,

used to spot problems with a certain, mold (by looking at the letter involved).

The above application is more logical. However, they might have served somewhat

as mold identification, since the letter certainly would pinpoint the source if

the defects in the insulator were noted at the end of the lehr. But, in later

insulators made on semi-automatic presses with multiple molds (as the Hemingray

No. 40), the shop numbers are not mold numbers, since each mold on the press would

have the same number.

There is probably no real reason why the letters were put

in a certain spot. It would be up to the whim of the engraver or the wishes of

the persons who had to read them when they came out of the lehr. Where the

letter appears in two places (skirt and crown), evidently it was originally

engraved in one place (skirt), and then someone thought it would be easier to

read in the other place (crown). Naturally the same letter would appear in both

spots. Since the letters do not always look the same, this shows that they were

no doubt put on at different times by different engravers. As for the total

number of letters used, that would indicate how many molds there were. The mold

shop foreman would have kept track of those for his own purposes.

Shop letters are often

backward in the glass, meaning that they were engraved in the mold in the normal

position. It was probably easier that way, and since the purpose of the markings

was as it was, it would make no difference. An example is the letter

"N", which is always backward. (See Figure 21, left) It is one letter

that is easily confusing. Some shop letters are hardly identifiable as anything.

But those incomplete or unclear markings served their purpose just as well.

As for the upside-down "L", could it have been meant as an

"F"? On some units with stronger embossing, one can see the center bar

of the "F", but it is very faint and somewhat wavy as though it had

been scratched in the mold but not finished properly. (But if it is an

"F", why wasn't it embossed in back? You can see in Figure 30 that

there's no "F" in the sequence of letters embossed on the back. I tend

to believe that no "F" was used deliberately, to avoid confusion with

the "E".)

Since the publication of my article in 1979, new information has surfaced

about a certain letter. What was once thought to be a backward "C" has

been identified as an upside-down "G". (I saw that beehive myself.) So

this discovery tends to throw off any previous pattern that seemed to emerge,

making eight letters that appear on the front, and seven on the back. (However,

if the upside-down "L" is an "F", and the upside-down

"G" is a mistake, that would make only seven each.) As for front

letters, five appear above the "H. G. CO." embossing, and four below.

(All letters on the back appear below the "PETTICOAT" embossing.) As

for colors, of those beehives with letters, certain colors seem to have certain

letters. Just the ambers always have letters, whereas the straight-sides (in any

color) never have letters. All other colors are found both ways.

More in Part 4 next month...