The Tennessee Glass Block

by Ray Klingensmith

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", May 1988, page 4

Back in August, 1972, an article written by Frank Jones appeared in CROWN JEWELS OF

THE WIRE. It was an informative account of how he was introduced to

the "Block Glass" insulator. I have recently completed a little more

research on these insulators, and felt it might be of interest to all

collectors. As Frank mentioned in his article, these insulators have gone by

many names, but I think the most widely accepted among collectors of today is

"glass block." While there was another find of this type of insulator

made in Selma, Alabama, in the early 1970's, and also a couple other individual

finds around the country in later years, I will not go into great detail on them

since my research centers mainly on the colored type found in Tennessee.

The insulators were found in an old railroad depot in Gallatin, Tennessee,

along with a broken threadless egg insulator. Frank mentions the depot was being

torn down and that the insulators were in a box located in one of the

storerooms.

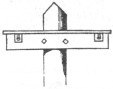

This type of insulator was one of the earliest used in this country. It was

designed in away that it fit into a bracket or a crossarm, its protruding lips

holding it securely in place. The wire could be inserted through the bent slot

and into the center cavity where it was held in place. The peculiar form of the

insulator prevented the wire from escaping. A book written in 1859 titled THE

TELEGRAPH MANUAL gives a detailed description of how these insulators were used:

An auger-hole the size of the glass is bored through the pole about two

inches from the end. With a chisel the wood about the auger hole is cut out,

which leaves a mortised opening for the insulator as seen in Fig. 1. Letter

A is

the insulator, with the flange opening; B is the projecting head; C

the groove or

hole for the wire, D one of two small boards nailed on the top of the pole to

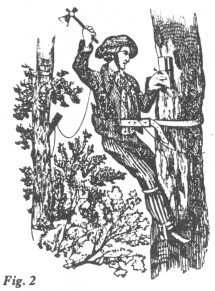

form a roof. When trees were used on the route of the line, a bracket was

attached to the tree, as represented in Fig. 2, excepting that the board roof is

not shown in the figure. This insulator allowed the wire to rend through, so

that whenever a tree fell upon the line, communication was not interrupted. When the wire is first stretched it is taut, but in a short time it becomes

slack by expansion, and whenever a tree falls upon the line the wire is not broken but carried to

the earth with the tree. If the wire does not touch the moist earth, the

telegraph continues to work without interruption. If however, the wire is

imbedded in the earth, communication will be stopped until the wire is elevated.

In forest provinces the open insulator has been found indispensable. In open

countries it has not been considered of any advantage.

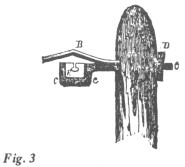

Fig. 3 represents another combination for insulation. It was adopted by

Messrs. O'Rielly, Kendall, Tanner, Shaffner, and others, and was considered on

its introduction as the most perfect for the purposes in view. A is the telegraph

pole. B an iron roof about four inches wide and six inches long from point of connection with

CC, from which point it is reduced

to an arm the same in size as CCC. The part through the pole is round and about

one and a half inches in diameter. D is a wedge or key to hold CCC in the pole.

E is the insulator which is two and one half inches long. The glass insulator

E

is set in the arm CC. The projections at the ends and the weight of the wire

hold it in the arm. B, the iron roof mentioned above, covers the glass, so that

the rain cannot make a connection with the earth. These insulators were well

approved and extensively employed, but in a few months they had to be taken off

and others substituted for them. They proved to be more disastrous than the

brimstone insulators. They brought ruin on every line that used them. The glass

E would easily break, and then the wire resting on the iron arm CCC gave the

current an earth circuit whenever the poles were damp; and if trees were used

the sap carried off the voltaic current. It was found impracticable to work successfully

a line one hundred miles with them.

It is impossible for the reader to comprehend the sad results that fell upon

the lines that used this insulator. Many thousands of dollars were lost in the

constant repair and loss of business. They had to be removed from every line

that used them. The telegraphers of the Northwest ever keep in sad remembrance

the brimstone insulator, and the telegraphers of the Southwest will never forget

the painful history of the iron insulator.

The Tennessee blocks represent an interesting part of the history of the

telegraph in this country. Within two or three years of the invention of the

telegraph, lines spread rapidly throughout the eastern states. By rnid-1847,

thousands of miles of wire had been constructed. Competition was fierce among

the then existing companies at that time. While most of the major cities in the

east were connected by wire, the Ohio Valley and cities to the south and west

were not yet serviced by this new means of communication.

At that time, the telegraph had reached Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was

decided to construct a line from Pittsburgh, through the Ohio Valley, to

Louisville and eventually to New Orleans. Two competing companies were involved

in a race to the Crescent City following that route, while still a third company

was constructing a line from Washington, D.C., through Virginia, the Carolinas,

Georgia and Alabama to New Orleans. I will not go into great detail on all three

of the companies involved, but rather will include here some information on one

of them, the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Louisville Telegraph Company, since it

is of interest to the glass block collector. This information was taken from

"The Telegraph In America" by James D. Reid, 1878:

The line was built

by Bernard O'Connor and Capt. John O'Reilly; was mounted with a single iron

wire, resting on square block glass insulators; poles, twenty-five to the mile.

It was completed to Cincinnati August 20, 1847, to Louisville, Ky., Dec. 29,

1847,

and was incorporated with a capital of $173,000. The office at Wheeling, Va.,

was opened July 8, 1847, by Henry C. Hepburn; Zanesville, O., August 5,

1847, by S. K. Zook; Columbus, O., August 11, 1847, by S. K. Zook; Dayton,

September 10, 1847, by W. J. Delano; Cincinnati, August 20, 1847, by S. K. Zook

and C. T. Smith; Madison, Indiana, Sept. 29, 1847, by Rufus Chadwick; Louisville,

Ky., Dec. 29, 1847, by Eugene S. Whitman.

The capital stock actually issued was

$138,400 or 2,678 shares. Of this about $35,000 was issued to Mr. O'Reilly, in

addition to $150 per mile for the construction of the line. In 1849 stock to the

amount of $35,200, or at the rate of $75 per mile, was issued for the the erection

of a second wire, the profits on which were about $40 per mile.

The competition for this area was presented by the New Orleans and Ohio

Telegraph company. This company was headed by an aggressive group of

businessmen. The 1500 mile route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans was divided into

five sections as follows:

|

RACE TO THE CRESCENT CITY |

Section

|

Location

|

Miles

|

Contractor |

|

1.

|

Pittsburgh to Wheeling

|

59

|

E. D. and E. M. Townsend |

|

2.

|

Wheeling to Cincinnati and

Lexington

|

401

|

Eliphalet Case aided by T. C. H. Smith |

|

3.

|

Lexington to Nashville

|

273

|

William Tanner and Taliaferro P. Shaffner |

|

4.

|

Nashville to Waynesboro

|

92

|

H. M. Watterson |

5.

|

Waynesboro

to New Orleans

|

658

|

John J. Haley and

William Lloyd |

By late 1847, both companies had reached Louisville, Kentucky, which at that

time was to a vast region to the north, the gateway to the south. Its important

location on the Ohio River generated great amounts of trade with New Orleans and

other important cities on the Mississippi. It was a radiating point for the

telegraph in linking towns of importance in all directions.

While the New Orleans and Ohio Telegraph Company was formed to build the

entire length of the line, a separate company was formed by the competition from

Louisville southward. It was known as the Peoples Telegraph. Henry O'Reilly was

responsible for raising money for line construction.

The following account, taken from Wiring A Continent (1947) by Robert

Thompson shows clearly the competitive force driving the workers of the two

companies on their way to the Crescent City:

The actual meeting of the opposing forces late in January proved to be more

like a relay race than a riot. Shaffner wrote Morse of the amusing encounter.

The O'Rielly hands, it seems, got a better start out of Louisville than had his

men. Pleased with their forward position, they boasted that the Shaffner

hands could never overtake them, a challenge which could not go unanswered.

"We were determined to do it," Shaffner wrote. "I had them notified that we were prepared to meet them under any circumstances. We were

prepared to have a real 'hug', but when our hands overtook them they only

'yelled' a little and mine followed and for 15 miles they were side by side and

when a man finished his hole he ran with all his might to get ahead, but finally

on the 24th, we passed them about 80 miles from here and now we are about 25

miles ahead of them without the loss of a drop of blood, and we shall be able to

beat them to Nashville if we can get the wire in time, which is doubtful.

While the

O'Rielly men might suffer temporary setbacks, they never lost their lead so far

as the over-all project was concerned. March found them in Nashville with

Shaffner trailing; June found them setting the last posts to New Orleans with

promises of wire to follow, while Amos Kendall's subcontractor on the

southernmost section had done nothing. The early success of the O'Rielly forces,

unfortunately, was more apparent than real; serious troubles were beginning to

make themselves felt. Their advance in the future was to be less rapid.

The Peoples Telegraph opened their line to Nashville on March 7th, 1848. The

following, taken from The Telegraph in America gives a further account of line

construction:

The building of the People's Telegraph line was committed to the care of Dr.

A. Sidney Doane, one of the early directors of the Magnetic Telegraph Company,

Charles G. Oslere of Pennsylvania, and Captain John O'Reilly, who pushed their

work with so much zeal that on March 7th, 1848, the line was opened to

Nashville, Tenn. Some idea of the condition of that first section may be

gathered from the fact that scarcely had the shoutings ceased which welcomed the

opening of the Nashville office, before a gap of fourteen days loss of

connection with the North was reported. From thence it was built southward

through Tuscumbia, Ala., Columbus and Jackson, Miss., and thence through Clinton

and Baton Rouge, La., to New Orleans. In his address to the editors and

merchants of New Orleans, Mr. O'Reilly said that he would ask for no subscription until the line was

built. This, of course, roused interest in his work and gave him great popularity, but it was the grave of his fortunes. The men

of New Orleans were in no

haste to take stock until they saw the fruit of the venture, and that fruit was

not tempting. The whole line was finished early in 1849. In its construction, it

was, as usual, built of indigenous easily obtained timber, with little regard to

permanence, and over long sections in Mississippi the wire was borne by brackets

nailed to trees.

An exception to this general character of the line was in

that part of it built along the levees below Baton Rouge, the poles for which

were of cypress sawn square, with the square block insulator on top. By one of

the fatalities incident to a hurried work in the hands of unskilled men, the

insulators, instead of being made of glass, were of glazed earthenware, imperfectly

vitrified, through the thin crust of which the wire soon sawed its way,

and left the soft pottery exposed to the rain. which soon soaked into the mass.

The reference to the porcelain blocks is interesting in that I'm not aware of

any of these having been found in the south. A small number of these have been

located on a very early line in the Sierras in California.

While the Peoples Telegraph did reach New Orleans ahead of the New Orleans

and Ohio Telegraph Company, it had its fair share of difficulties. In May, 1850,

a meeting was held in Louisville among the investors, builders and managers of

The Peoples line and it was decided to lease the line. More financial problems

were encountered in the future, and the company was leased, to a group of men

including George Douglass, Norvin Green, Thomas Carter and others. This group

was known as the New Orleans and Ohio Telegraph Lessees. Further financial difficulties

arose and the line was sold at a sheriff's sale. The South-Western Telegraph

Company was organized under an act of the Legislature of Kentucky, passed

December 22, 1859, and by a vote of the stockholders January 6, 1860.

The following is also taken from The Telegraph In America and is a possible

explanation as to why the blocks were located in a railroad depot:

Immediately on the organization of the N.O. & O. Tel. Lessees, in 1854,

and in following years, a general and thorough rebuilding of the whole structure

was commenced along the new railroad routes, now happily for the S. W. Telegraph

Company, pushing their way from Louisville to New Orleans, and out to Memphis.

The railroads gave the property protection, and all the forest routes were

abandoned. Every dollar of earnings was thus devoted until the whole structure

was thoroughly rebuilt. It then at once took position of first-class rank among

the telegraphic forces of the country.

The fact that the lines were eventually rebuilt along railroad routes rather

than through forested routes could explain why the blocks were in the railroad

depot. Frank Jones, in his 1972 article, mentions the depot was built in 1850 and

this particular railroad having been completed in 1857. Of all the blocks found

in the depot, only one of them showed any signs of use. It is the bubbly opaque,

longer style and has some abrasions in the groove. All of the others appear to have never been used. I would guess the

insulators were extras distributed along the route at the time of initial (1848)

construction to be used as replacements as others were broken on the line. It is

possible they were stored elsewhere for a period of time and removed to the

depot after it was built. They could also have been manufactured at a later

(early to mid 1850's) time period if this style of insulator was kept in use.

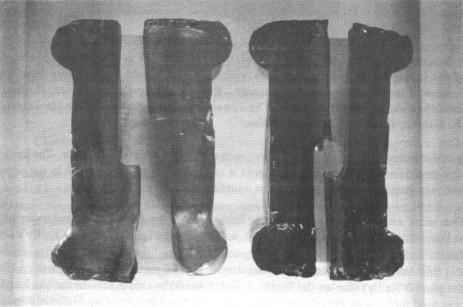

The insulators found in Gallatin were all colored. It is interesting to note

the variety of colors found ranging from a deep amber to various shades of

green. Following is a listing of those found: 7-up green, olive green, olive/7-up

green, golden amber, blackglass red amber, bubbly 7-up green, opaque (milky)

green in two differing colors, a color similar to 7-up but more clear and

brighter, a true green similar to emerald, bright "crystal blue" (not

aqua) and the longer type bubbly opaque one. The "crystal blue" one is

interesting in that the notch in the top is facing the opposite direction as the

notches in all the others. All of these colors remain rare today, some of which

are still one-of-a-kind. The 7-up green was the color in which most of the

insulators were found in this group, but even they remain very rare in the hobby

today. It is interesting that nearly all of the blocks found in other areas are

aqua, and that all of the Gallatin items were colored.

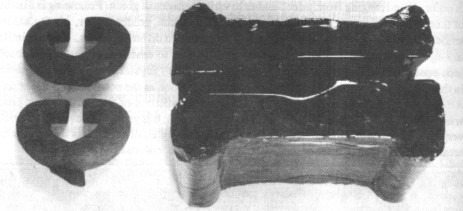

On the left is one of the aqua blocks found in Alabama. At the right is the

only known

complete block with left handed wire slot. All others known have a

slot which bends to the right.

Most of the aqua blocks in collections today came from the discovery of a

dump in Selma, Alabama, which I believe was on the route of the Washington and

New Orleans Telegraph Company line between those two cities, and was the third

line referred to earlier that was being constructed to the Crescent City in the

1840's.

A few aqua blocks have also been found in Alabama and a colored block has

also recently been purchased in that state and is assumed to have been used

there. It is lime green and is one-of-a-kid as of this writing.

Also found in the depot with the blocks were some iron devices used to hold

the line wire rigidly within the block. As was mentioned previously, the wire

could pass freely inside the insulator. If one desired to have the wire held

firmly inside the insulator, a heart shaped iron piece was placed at each end of

the insulator and a wedge was driven through it, binding the wire against the

iron piece.

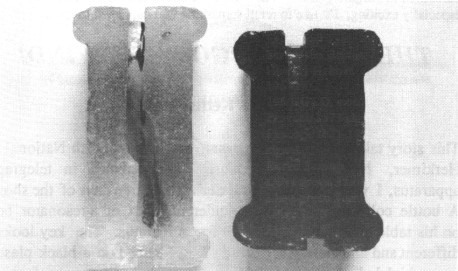

A deep red amber block with two of the cast iron pieces which were used, one

at each end of the insulator, in conjunction with wedges to firmly hold the line

wire from any horizontal movement inside the insulator. Without the iron pieces

in use, the black would be a slack wire type insulator. The iron ends were also

found with the blocks inside the Gallatin, Tennessee, railroad station.

It is also interesting to notice the difference in the length of these

insulators. The longer type would probably adapt better to use in a crossarm

where greater width in the wood arm was required, and the shorter type adapting

to use in a tree bracket.

One must wonder if the two competing lines through the Ohio Valley and

eventually to Louisville, Nashville and New Orleans, both made use of glass

blacks. O'Reilly's line from Pittsburgh to Louisville, according to Reid in The

Telegraph In America, shows the line having used them. Also mentioned are the

porcelain blocks used on The Peoples (O'Reilly) line in the South. I feel it

would be safe to assume the block style was used throughout the original

construction on this line (including Gallatin through which this line passed).

At right is a one-of-a-kind snowy opaque block of the longer style which

would adapt

to cross arm application. At the right is a regular size Tennessee

block in a

beautiful milky-opaque green.

It is quite possible that blocks were also used on the New Orleans and Ohio

Telegraph Company line that also followed much of the same route from Louisville

to Nashville. So the Gallatin blocks could have been made for either company.

There has been great speculation as to where these insulators were made. It

would seem likely they were produced somewhere near the location

the line was built so as not to have a need to transport material any great

length. We must remember this was in the 1840's and railroads were only

beginning to see construction, and then only in the eastern states. Materials

were carried either on major rivers or on wagon roads. Reid makes reference in

his book to the most likely source of the blocks:

Charles T. Smith, who was a careful reader of current electrical literature,

called attention to the necessity of care in the preparation of glass, based on

an observation by Faraday, on whose experiments the most absolute reliance could

be placed. It led to a marked improvement in insulation, even with an awkward

and objectionable outward form. At that time, all insulators, for western lines,

were made at the Novelty Works, Pittsburgh, Pa. Faraday's note is as follows:

"In experiments upon the manufacture of glass for optical purposes, I have

found that with such as contained no alkali, but consisted of silicia, boracic

acid and oxide of lead, the insulation was so perfect as to equal if not surpass

that of lac resin. This glass is not at present in use, but may hereafter,

because of this and other properties, be very useful in electrical

investigations"

Perhaps to say all insulators for western lines were made at the Novelty

Works is an overstatement. One would guess the lines further north in Ohio,

along Lake Erie, could have had insulators produced elsewhere, but it does lead

one to believe the Novelty Works did most likely produce the blocks found in

Gallatin. These are a colorful, interesting group of insulators that represent a

lot of the history of man's attempt to be linked with better communication in

the very early days of the telegraph industry.

|