"Our present system of insulation is a positive disgrace to the

scientific ability of our American telegraphic engineers." G. Prescott,

1866

During my years of collecting Hemingray insulators, I often wondered about

the conversations that had gone over the wires carried by these glass jewels.

Today we think of telephone conversations as the major impetus for the

construction of pole lines with wires and insulators, but what really got it

started was the telegraph. Interestingly enough, the first telegraph line was

buried, not aerial. In 1843 Samuel Morse began construction of an experimental

line along the rail line between Baltimore and Washington using wires in buried

lead pipes. The copper wires, however, were not properly insulated and the

entire route had to be rebuilt above ground on wooden poles. In 1844 the line

was completed and Morse sent the first telegraph message, "What hath God

wrought?", from the Supreme Court Chamber in Washington, D.C. to Baltimore

over the 40-mile wooden pole line route. The age of telecommunications was born

and along with it the urgent need for insulators and telegraph equipment. By

1850, 22,000 miles of telegraph lines had been strung to points as distant as

Washington, D.C., New Orleans, Iowa, Maine and Canada. By 1866, there were more

than 50,000 miles of mostly iron lines in operation having more than 1,400

telegraph stations and employing upwards of 10,000 operators and clerks. That

same year an estimated five million messages traveled over these facilities,

producing an annual revenue of $2.2 million. Of interest to insulator collectors

is that in 1866 an estimated 1.5 million insulators were already in service.

|

COVER: Complimenting Jerry Post's article on telegraph

equipment (page 3 0 f this issue) are examples of a key, relay and sounder

that are in Jerry's personal collection. Jerry lives in Colleyville,

Texas.

|

The bane of this expanding telegraph system, however, was the insulator

supporting the wires. George Prescott, a noted scientist, wrote in 1866,

"Our present system of insulation is a positive disgrace to the scientific

ability of our American telegraphic engineers." The chief complaints being

that the insulators, especially when wet, allowed the electrical current to

escape to the supporting wooden post, and that the insulators were easily

broken. Early telegraph insulators consisted of glass plates, bureau knobs and

simple glass blocks with notches to hold the wire in place. In 1851 a patent was

issued to Nelson Goodyear for an insulator made of rubber. Insulators of wood and pottery were also developed to

overcome the objections cited by Prescott. By the mid-1860s, the majority of

insulators were glass shaped much as an insulator collector knows them today,

sans threads and drip points. For many years it was up to the developing

technology of the telegraph apparatus to work around the shortcomings of the

insulators.

First, let's talk about the telegraph apparatus that makes up the

telegraph network. Then we'll discuss the items from the perspective of the

telegraph collector. Telegraph equipment can be grouped into four broad

categories: 1) keys, 2) sounders, 3) relays, and 4) auxiliary items.

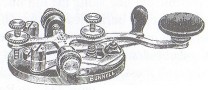

The

telegraph key (Figures 1 and 2) is the basic telegraph transmitter, a switch

with contacts that make (close) or break (open) the telegraph circuit to the

distant receiver. The key's electrical contacts are held open by a spring. When

the operator presses on the key's knob, the contacts are closed and the circuit

is completed sending the familiar dots and dashes of the Morse Code. From a

historical perspective, keys can be grouped into pre-Triumph (1844-1881), and

post-Triumph, (1881 to present.) The Triumph Key (see Figure 1) was patented

in 1881 by Jesse Bunnell who had been a telegrapher during the Civil War.

Bunnell named it Triumph because he thought his new stamped steel lever would

triumph over the design problems of existing keys that

used a heavy brass lever with steel pivots pins which eventually worked loose.

Fig. 1. The Triumph Key.

Keys were designed as either legless (Figure 1) to be attached to a table, or

leg keys (Figure 2) with bolts to be permanently attached to the table with the

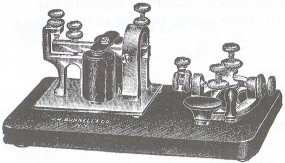

wires connected underneath. Sometimes the key and sounder (see below) were

mounted on the same base as seen in Figure 3. Referred to as KOB (key on base),

these combination sets were often used for training. There were, of course,

numerous other designs and manufacturers of keys.

Fig. 2. Telegraph key

with bolts

for attachment to a

table.

The telegraph sounder (Figure

4) is the receiving instrument that transforms the electrical pulses from the distant office into a click

when its electromagnetic coils are energized and a clack when the magnets

are released. Each electric pulse from the distant key thus produces an audible

click-clack sound which is interpreted by the receiving telegraph operator as a

dot or dash. Sounders can be identified by their two vertical electromagnets.

Sounders may be either mainline or local. The mainline sounder was connected directly to the telegraph wire from

the next office. Local sounders were powered by a local battery within the

telegraph office in conjunction with a relay to detect the pulses from the

distant office.

Fig. 3. Key on base combination set.

Mainline and local sounders look much alike although the mainline may be

somewhat larger.

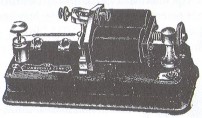

A telegraph relay (Figure 5) is a sensitive electromechanical repeater used

on long telegraph lines, generally more than twenty miles. The weak signal from

the distant office was rejuvenated by the relay and passed to the next office along the line. A relay is more sensitive than a

sounder and can be identified by its two horizontal electromagnets and

horizontal tension spring.

Fig. 4. The Telegraph Sounder.

Auxiliary equipment includes batteries, switchboards,

test sets, resonators, etc. There are literally hundreds of these items for the

serious collector.

Fig. 5. The Telegraph Relay.

As with insulators, the price for a telegraph item varies

based on age, condition and how rare or unique the item is. Unfortunately,

there is nothing for the telegraph collector that even begins to approach the

insulator Consolidated Design (CD) identification system, or McDougald's Price

Guide for Insulators. Tom Perera in his book, Telegraph Collector's

Guide,

states that "most buyers and sellers simply do not know what telegraph

items are worth." Despite their historical and scientific significance,

telegraph items are among the few remaining undiscovered collectibles. Ebay and

similar auctions, of course, may soon change all of this. Prices for common

keys, sounders and relays currently range from $25 to $150. Recently a particularly rare

telegraph key sold for $1,200. Prices for auxiliary telegraph apparatus are even

more variable since few people know what it is or how rare it may be.

Again, as

with insulator collectors, there is much discussion among telegraph collectors

concerning how much, if any, restoration should be done. Most collectors prefer

to keep the item in its original condition doing only what is necessary to stop

any further deterioration. But, with all that brass, a rosewood base and black

iron platform with a gold pinstripe, it is hard to resist the temptation to

restore the equipment. And, yes, it really would look great on your desk next to

a favorite insulator. The telegraph collector should be aware that a complete

restoration takes lots of work, may obliterate historical markings and should be

avoided.

Although not as numerous as the millions of insulators produced since

the 1840's, thousands of telegraph keys, sounders and relays were manufactured

to serve telegraph and railroad offices in virtually every town in the developed

world. Today, many of these items can be found at swap meets and on the Internet

auctions. They make an appropriate adjunct to our insulator collections, and we

owe a tip of the hat to the telegraph network and equipment that got it all

started more than 160 years ago. For more information on the history of

telegraphy and collecting telegraph apparatus, refer to:

The W1TP Telegraph

Museum at: http://w1tp.com

or

The Telegraph Office at:

http://fohnix.metronet.com/~nmcewen/ref.html