MAC's Believe It Or Not!

by John McDougald

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", June 1993, page 12

As a number of you already know, I started back to school in January in

preparation for a second career. It must have been the academic influence that

perpetrated the following dream sequence:

|

Instructor:

|

Mr. McDougald!

|

|

Mac:

|

Yes?

|

|

Instructor:

|

Please construct a sentence

with the following two words in it - - Hemingray and threadless.

|

|

Mac:

|

"Hemingray never made a threadless insulator!"

|

|

Instructor:

|

The

sentence construction is excellent. Unfortunately, you don't have your facts

straight.

|

|

Mac:

|

What do you mean? I've been collecting insulators for 25 years. I

know what I'm talking about.

|

|

Instructor:

|

You think so? Well, take a look at

this.

|

A dream! Yes, the events described above were a figment of my imagination, but

they occurred AFTER I saw my first Hemingray threadless. Pictured (on the

following page) is the first, to the best of my knowledge, CD 732.2 embossed

(F-Crown) PATENT/DEC 19 1871 (R-Crown) 1. The shape is identical to the CD 131.4, the old Hemingray Number 1 style, except for being threadless. It is a three

piece mold (CD 131.4' s came in both two and three piece molds). As often

happens, news, and in this case good news, often comes in bunches. In addition

to being threadless, it is light sun colored amethyst (SCA) and the pinhole

formation appears to meet the specifications of the Floyd Threadless Patent.

The Floyd patent has been covered twice in Crown Jewels of the Wire (7/78 and

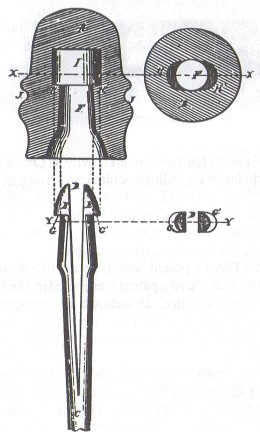

4/86 articles by Ray Klingensmith). so I'll only comment briefly on it. The

principal is fairly evident from the accompanying drawing. The intent was to

form a larger cavity at the top of the pinhole and use a pin that would expand

when it reached the top. It would lock in place due to the ledges HH' of the

insulator and the shoulders GG' of the pin.

Why didn't Floyd's patent. which

seems like a pretty good idea at first, catch on? First of all, Floyd's patent

was issued in 1867, so the threading process was already in existence. In

addition. in correspondence with N.R. (Woody) Woodward. he indicated that the

expense and inconvenience associated with the development of the mandrel for

this type of pinhole would probably be prohibitive.

The insulator itself sheds

some additional light on potential problems. While the top half of the pinhole

is oval in shape, per the patent, there aren't really any ledges HH' for the pin

to lock over. The formation of the top of the pinhole is crude with lots of

stress fractures. This indicates to me that when the mandrel was expanded (by

whatever method) to form the cavity at the top of the pinhole, it wasn't done

under pressure and must have been withdrawn quickly because the glass had a chance to run before it solidified.

As a result, the transition to the larger cavity is gradual, rather than sharp

as it is shown in the drawing. I suspect that even if I had a pin made to

Floyd's specifications, it would slip in and out of the pinhole.

Ray speculated

in his earlier articles that Floyd probably had actually produced some samples

(confirmed by earlier finds) based on the way he worded his patent application.

He also speculated that Hemingray may have been involved in that production.

This find confirms that suspicion. In many ways, I feel like the discovery of

this insulator is one of the "missing links" in the history of

insulator production. It helps close the gap in that era when conversion from

threadless to threaded was taking place, and it ties another patent to a known

insulator manufacturer. For those of you who will be able to attend, this

special insulator will be on display at the Denver National. Stop and visit at

the Crown Jewels of the Wire table and take a look.

I am once again reminded

that in this hobby, it's wise "never to say 'never'"! Oh, by the way, one

more thing -- this jewel was found on a pin, still up in the air, mounted on a

house - BELIEVE IT OR NOT!!!

|