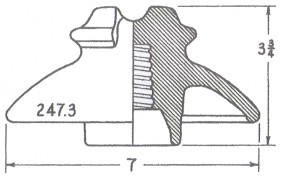

New Fred M. Locke Glass Insulator -- CD 247.3

by Elton Gish

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", May 2002, page 3

I attended the CBIC show this year in Maryland Line, MD organized by Larry Novak. It was a wonderful show with lots of people crowding the fire

hall most of the day. As if it wasn't exciting enough, Ken Wehr walks up with an

interesting power insulator that had lots of patent dates circling the top

skirt. He was probably as excited as we were after seeing the interest over his

new find and after he learned it probably would be assigned a new CD number by

N. R. Woodward - that is if I could find room somewhere to make a shadow profile

of it. That would take an unobstructed 30-foot run to shine my flashlight on the

insulator. The people making wonderful food all day at the snack counter

directed Ken and me to another building, unlocked the door, and allowed us to

set up the simple profiling device (pane of glass stuck in a board). The room

felt near freezing from the recent weather change, but in less than 10 minutes

we were finished and back in the warm fire hall. Ken was cradling his rare jewel

a bit more closely now. He said he bought the insulator for $25 just two weeks

earlier in an antique shop outside Parkersburg, WV - proof that rare new

insulators can still be found.

N. R. Woodward assigned CD 247.3 to Ken's new

style of Fred Locke insulator. The color is straw color with a slight lemon

tint. The condition is mint except for a small bruise on the outer skirt edge.

In typical Fred Locke fashion, the embossing is upside-down and circles the

skirt:

PAT'D BY F.M. LOCKE VICTOR, N.Y. (front skirt)

MARCH 31, 1914, FEB 2, 1915. NO.7. (back skirt)

OCT 12, 1915.

Many of you are probably wondering what Fred Locke has to do with glass

insulators. Yes, he is the "Father of porcelain insulators", but when

he "retired" in late 1904, he continued to work to improve the quality

of porcelain insulators. This entire story complete with photographs of several

styles of glass insulators yet to be discovered can be found in my book, Fred M.

Locke: A Biography.

Before Ken's discovery, only two Fred Locke glass pin-type insulators were

known: CD 241 and CD 178.5.

New style of Fred Locke glass insulator: CD 247.3.

This photo shows part of the embossing and the

"NO.7" indicating

several styles were made.

After Fred Locke "retired" from the Locke Insulator Mfg. Co. in

December 1904, he continued to work for them as a consultant and was often seen

in the factory. He purchased a large home at the end of Main Street in Victor in

1900 and added a large laboratory on the right side after he

"retired". There he experimented with ways to improve the quality of

the insulator material used for porcelain insulators. He filed several patent

applications in 1905 -1909 for improvements in porcelain formulas initially

using feldspar flux and later with the addition of boron. Probably quite by

accident he developed a formula that was actually a new form of glass. Glass is

not that much different in composition than porcelain.

In the June 24, 1909

issue of the Electrical World, Fred Locke announced 'his new insulating material

calling it "Transparent Porcelain" (he was still trying to make

porcelain insulators). The article stated that "The base [of the new

material] is aluminum silicate [feldspar}, and the material can be melted and

cast in the same manner as glass. Two of the remarkable features are the

temperature changes it will withstand, and its high specific inductive capacity:

These, together with great mechanical strength and high resistivity, ideally fit

the material for all classes of insulation." Two photographs still in the

Locke family (shown in my book) show a modern looking glass suspension

insulator. One of the photographs appeared in the 1909 article. Both photographs

clearly show the glass was darker and filled with what appears to be air

bubbles. Only one specimen from this time period is known, which is the flared

middle skirt from an insulator similar to the 3-part Brookfield No. 331. In

fact, a photo of that Brookfield insulator was with other Fred Locke family

photos and the embossing "No. 331" can be clearly seen. The color of

the flared middle skirt is dark straw. While the glass does have a myriad of air

bubbles (see photo on following page), what gives the glass its unique

appearance is the fairly uniform dispersion of tiny flecks of white, which may

have been the feldspar flux. It is understandable why he called it

"transparent porcelain". The characteristics of the glass are unlike

any glass known today.

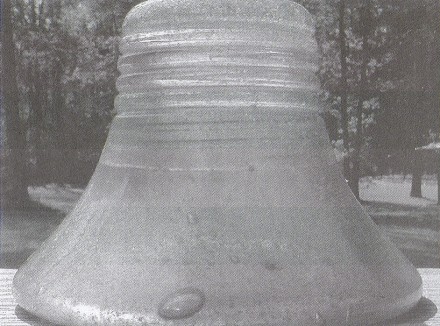

This is the only known example of Fred Locke's

"Transparent

Porcelain". It is the middle skirt of a style

similar to the 3-part

Brookfield No. 331. Note the heavy

flock of white particles and the darker shade

of the glass.

Fred Locke had insulators made from his early glass patents by Brookfield in

1908-09 and possibly later. Two glass patents were granted in 1908, one in 1909,

and another patent in 1910 for the suspension disk that could be linked together

with cap and pin for higher voltages. Either problems with the Brookfield-made

insulators or Brookfield's unwillingness to make insulators using Locke's

specially formulated glass resulted in limited production. I suspect the glass

was brittle and Locke experienced difficulty finding customers willing to try an

insulator that was radically different.

Fred Locke was not one to rest on his laurels. He continued work to improve

the new insulating material. On March 9, 1909, he filed a patent application for

the addition of boron in both glass and porcelain to improve the thermal and

electrical properties. For unknown reasons, the patent application stalled at

the patent office. The application was divided into additional applications

filed in November 1913, March 1914, June 1914 (boron in a porcelain base), and

January 1915. Another patent application filed on May 19, 1909, claimed the

benefit of adding boron to both glass and porcelain base ingredients. The patent

granted on March 31, 1914, stated the composition may be varied and "it may

be made either opaque or transparent, according to the degree of heat to which

it is subjected in firing." This may explain the light white opalescent

color on CD 178.5 and at least one specimen of CD 241. Research at Corning by

the developers of Pyrex revealed the "peculiar white streak" was the

result of fluoride present in the glass.

The original March 9, 1909 patent

application, its resultant applications from dividing the patent, and the May

19, 1909 application granted on March 31, 1914, collectively make up the five

patents represented in three patent dates embossed on CD 241 and CD 247.3: March

31,1914 (two patents), February 2,1915 (two patents), and October 12, 1915 (one

patent). All five patents claim the use of boron in glass and the benefits of

reduced cracking from temperature changes and improved electrical insulation.

One patent claimed increased resistance to electrical puncture. The two

specimens of CD 178.5 do not have the October 12, 1915 patent date, which

indicates they were probably made between February and October 1915. Corning

Glass Works made all three styles for Fred Locke.

Several more patents were

granted for other glass formulas, totaling 15 patents in all, from 1908-1922.

Most of the glasses were boro-silicate types very similar to Corning's Pyrex

glass for which a patent was granted them on May 27, 1919 on an application

filed June 24, 1915. As stated in the patents, some of the Fred Locke formulas

produced an opalescent glass and others were clear or tinted. There are

articles, in trade journals from 1915 to 1916, which refer to the glass as

"Boro-porcelain" and "Boro-silicon". Fred Locke could not

quite get away from the fact that he had been experimenting with ways to improve

porcelain and accept that he had discovered a new glass formula superior to

porcelain with regard to resistance to cracking from temperature changes. Some

of Fred Locke's letter to Corning in 1916 and 1917 had a letterhead advertising

"Boro-porcelain" insulators.

Fred Locke was having glass insulating tubes, glass pin-type insulators, and

modern styles of glass suspension insulators made by the Corning Glass Works

(see the various photos in my book). Confirming evidence of this fact was

uncovered in the Corning archives after my book was published. Corning announced

their new glass baking ware and other dishes in Boston in the third week of May

1915 (just prior to their patent application for Pyrex). Fred Locke probably

received his first order of insulators from Corning earlier that same year. The

use of Fred Locke's patents on his insulators is puzzling in the light of one

letter he sent to Corning, "...please make me 1000 #8 insulators from tank

glass G702-EJ" (note CD 247.3 is embossed "NO.7, so conceivably he had

Corning make eight different styles). It is not known what the "G"

stood for, but "702-EJ" was Corning's basic Pyrex ovenware-labware

formula which went unchanged until the early 1980's.

Corning was making Pyrex

heat resisting cookware and other dishes in early 1915 prior to the patent

application. On May 22, 1915, Fred Locke wrote to Corning asking them for a

selling agency and two sets of dishes (one for his home use and one for sales

samples). He thought, "I believe the dishes handled together with the

insulators will help to advertise them both." Corning's letter to Fred

Locke on May 24 stated, "It is too early yet for us to consider any selling

agencies for glass baking dishes. We are having the first demonstration in

Boston this week (at Jordan Marsh) and it will be some weeks before we know more

definitely just how the trade will be handled. If you wish us to send you...a

full set of dishes, please let me hear from you but I assume under the

circumstances you do not care for an extra set."

In early July 1916,

Corning refused to make any more insulators for Fred Locke. Evidently legal

questions arose concerning Corning's patent application for Pyrex glass and Fred

Locke's similar glass formulas covered in his various patents and test melts.

Fred Locke was shut off abruptly without any way to fill orders for his

insulators.

Probably just as well since the practicality of Fred Locke's

suspension insulators was in question, but he was working to make appropriate

design changes. A letter from an engineer in Italy dated July 1, 1916 stated,

"... the mechanical resistance is too little; the breakage took place in

the trials we made were not due to lack of cement, or length of bolt, but to the

material itself, in the thickness [of the glass) between the cap and the

bolt." Their power lines experienced heavy weights of ice making it

necessary for them to specify suspension insulators that would withstand a

strain of 11,000 Ibs., which Fred Locke's insulators would not tolerate. If he could redesign

the insulators with a reduced thickness between pin and cap and the insulators

could pass testing at the Pittsburg Testing Laboratory in New York City, then

they would agree to purchase 6,000 suspension insulators.

On July 25, 1916, Fred

Locke wrote to the Vice President of Corning, A. A. Houghton, who was on summer

vacation in Massachusetts, asking his help in getting the company to fill his

order for insulators. He had been trying for over a year to sell insulators to

the company in Italy at 10 cents per pound and the Toronto Power Co. was ready

to place a trial order. He also mentioned "tubing or special work".

We

do not know what happened next other than Corning continued to refuse making

insulators and other glass items for Fred Locke. It was at this time that Fred

Locke became convinced that Corning had stolen his patents and used them for

Pyrex. In February 1917, there was correspondence between the two and a meeting

in Corning, NY to discuss a proposed contract whereby Corning would pay Fred a

fixed amount for rights to his glass patents and annual royalties. Corning was

stalling because their lawyers were out of town and this infuriated Fred. A

Corning letter dated February 27, 1917, was very interesting. The writer

discusses the difficult negotiations with Fred. It mentions a letter from Fred

dated February 26, The letter said they will look into Fred's past judgments

from other unrelated disputes and had this most interesting comment, "I

also have to report that in conversation with Frank Brookfield, of the

Brookfield Glass Company last week, I was told that they have some sort of an

agreement with Locke which gives them rights in the matter of boro-silicate

insulators. I met Brookfield, who was a classmate of mine, at a Glass Dinner,

and he said that he would be glad to give me full particulars when I am next in

New York." Corning was concerned about Fred's claim of a better offer from

another glass company for his patent claims.

Fred Locke met with Corning on

March 2, 1917 to discuss the contract details further. He proposed a $10,000

initial payment and $7,500 annual royalty that could be reduced to $5,200 if the

rights to porcelain were removed. The letter detailing the discussion with Fred

stated, "I am convinced that he firmly believes we have stolen certain

inventions from him, and in return he has done his best to steal from us;

working, apparently on the Prussian principle that one wrong justifies

another." Corning said they were making trial melts for Fred some time in

July 1914 when the first insulators were produced on a trial basis. In one of the later trial melts, insulators were

produced but were never shipped to Locke because it "was closer to Pyrex than

any other glass formula which he submitted." The final comments about the

meeting are interesting, "And I do not see, at the present time, any

possible way by which Locke can do us any damage except that if he sells out his

[patent) claims and pretensions in glass composition to some competitor with

plenty of money he might give us considerable annoyance for a time." It is

obvious at this time that the follow-up discussion with Frank Brookfield

revealed that Brookfield had little interest in pursuing insulators made with

Fred Locke's glass.

Fred Locke filed a suit against Corning in October 1917

alleging patent infringement. Details of that action and the outcome are still a

mystery, but the matter was apparently resolved. An alumino-silicate glass

patent granted to Fred Locke and his son, Fred J. Locke, on March 10, 1925 was

licensed to Corning. It was used for Pyrex Flameware percolators, double

boilers, and dishes starting in 1936. This same glass is used today in stovetops

and windows in all of the space vehicles including the Space Shuttle.

- - - - - - - - - - -

With all this talk about patents, some of you may want a bit more basic

information on patents. Patents have been granted by the U. S. government as far

back as 1790; however, the current patent numbering system for utility patents

was started in 1836 with -- patent No. 1.

There are three types of patents:

Utility patents (sometimes referred to as "Letters Patents") may be

granted to anyone who invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine,

article of manufacture, or compositions of matters, or any new useful

improvement thereof. Utility patents are for a period of 17 years and cannot be

renewed. If a serious omission or error in the patent is promptly discovered, it

may be corrected and a Reissue Patent granted with a later date than the

original patent. Such was the case with the Cauvet patent of July 15, 1865. It

was reissued on February 22, 1870 under reissue patent No. 3,847. The patent

term was altered in recent years to 20 years from the date the patent

application was filed with the Patent and Trademark Office. Since it takes two

to three years to secure a patent, this new rule does not materially affect the

term of the patent.

Design patents may be granted to anyone who invents a new, original, and

ornamental design for an article of manufacture. At one time, the term of the

design patent was for periods of 3-1/2, 7, or 14 years. The typical term and

current term is 14 years and may not be renewed. In the case of insulators, some

design patents were obtained (especially on guy strains) where no novelty was

involved other than a specific shape of the insulator.

Plant patents may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers and asexually

reproduces any distinct and new variety of plant. The patent term is 20 years

from the date the patent application was filed with the Patent and Trademark

Office. The right conferred by the patent grant is, in the language of the

statute and of the grant itself, "the right to exclude others from making,

using, offering for sale, or selling" the invention in the United States or

"importing" the invention into the United States. What is granted is

not the right to make, use, offer for sale, sell or import, but the right to

exclude others from making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing the

invention. In general terms, a "utility patent" protects the way an

article is used and works, while a "design patent" protects the way an

article looks.

U. S. patents afford no protection in foreign countries, but

"International Union" agreements give the inventor priority in filing

of foreign patents on the item. The inventor need not manufacture or operate

under the patent, but he must mark the patent date or number on what is produced

and must stop infringers, otherwise his monopoly lapses.

Trademarks were first registered in 1870. They are good for 20 years and can

be renewed for an additional 20 years at the time of renewal as long as it is

still of value to the company. A trademark is a word, name, symbol or device,

which is used in trade with goods to indicate the source of the goods and to

distinguish them from similar goods made by others. A service mark is the same

as a trademark except that it identifies and distinguishes the source of a

service rather than a product. The terms "trademark" and

"mark" are commonly used to refer to both trademarks and service

marks.

The Patent and Trademark Office issues weekly an Official Gazette, which

gives an abridged description of each patent during the week. Patents and

trademarks are always granted on a Tuesday. Dates found on articles that are not

a Tuesday, are not associated with a patent or trademark. If a Tuesday falls on Christmas or some other holiday,

it does not preclude granting of patents. There are 52 issues of the Official

Gazette every year without exception.

Copies of patents and trademarks may be

ordered from the Patent and Trademark Office for a price of $3 each. Or, you may

view and print a copy from their web site for free. The web based patent archive

is not searchable by text prior to 1976. Years 1790 to 1976 are searchable only

by number and classification. I have copies of over 1200 insulator related

patents, 57 design patents, and probably all of the trademarks. Copies can be

ordered from my Insulator Research Service for $1 each. Quantity discounts can

be arranged. Copies are furnished free for people working on a display or doing

research that will result in a published article or book.

The terms "patent

pending" and "patent applied for" are used by a manufacturer or

seller of an article to inform ,the public that an application for patent on

that article is on file in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. In some cases,

insulators are embossed or marked with these terms, but a patent was never

granted.

Only about 70 glass CD styles and fewer porcelain styles were made

based on a specific patent. No patent was granted for threadless insulators, the

flint Elliott styles, the wood covered Wade, or other early pin-type insulators.

For more information on patented CD styles and other related patent information,

go to the following web sites:

http://www.insulators.com/irs/

and http://www.nia.org/Timeline/index.htm.

For additional patent information, try Jack Tod's book, Insulator Patents:

1880-1860.

|