Porcelain Insulator News

by Elton Gish

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", May 1998, page 14

We usually discuss unipart or multipart pin-type porcelain insulators in PIN.

This month I would like to present a few unusual items that do not fall in this

category and which you may find interesting all the same.

The first item was

reported by Phillip Gillham (Laredo, TX) and it is not exactly an insulator. It

appears to be a decorative pottery guide plate for two electrical wires entering

a building through a wall. The two white, unglazed wall tubes shown in the

photograph fit nicely in the two holes; although, they appear to be more modern

than the guide plate. The guide plate (5-1/2" x 10-3/8" x 1-7/16"

thick) is made of pottery with a rich brown glaze and weighs 4-1/2 pounds. Note

the French word "CHAUFFEUSE" impressed in the center. This could be

the name of the company who made it, but I have a suspicion that it refers to

the intended purpose. We all know the word "chauffeur" refers to

someone driving a car for another person or more basically assisting or guiding.

Could the root word mean assist or guide? Perhaps someone with a background in

French could help us.

Phil got this unusual item from a friend who offered the

following background: "We understand that this clay tablet was used to

space the two wires used in domestic wiring in the late 1800' s. At that time,

the insulation was not as good on exterior wiring as it is today and wires

chaffing from wind action was a problem. This "chauffeuse" was found

when a farmer plowing near the site of an old plantation home near Savannah, GA

caught a copper wire. He found the insulation nearly gone on the wire. Upon

digging he unearthed this tablet and parts of two others strung on the wire. This information was provided by the lady in charge of

the antique shop in Brunswick, GA where we purchased this tablet." I'm not

sure how the "tablet" was mounted on the wall if it was a wooden wall.

Perhaps it was a brick wall in which case the "tablet" could have been

cemented to the brick. I would appreciate hearing from anyone who has additional

information on this unusual item.

Unusual "tablet" guide for electrical wires entering a building.

John de Sousa (NIA #419) reported the next insulator. I do not know exactly

how it was used. It is similar to U-190 which has a cap with a metal rod

cemented in it. I have seen the top of John's odd insulator which looks similar

to a standard pin-type insulator but this is the first time I have seen the

large bottom part. Please let me know if you have any idea how this was used.

Odd 2-part insulator with pretty rusty brown glaze.

The next item is not an insulator but its use is critical in the manufacture

of porcelain insulators. A number of these have been dug up over the years at

the Pittsburg dump and perhaps collectors have found them at other porcelain

dumps, too. They are called Seger cone-plaques and were placed at various

locations in the firing kiln to indicate proper firing temperature. The older

plaques are handmade of special clay with cones stuck in the clay. Newer plaques

came preformed with holes for the cones. The composition of each cone is

different so it sags at a specific temperature and each cone is stamped with a

reference number. I recently acquired a copy of "The Potter's Corner" published by Locke in 1952 when it

was a department of General Electric. The booklet is a series of papers written

by Walter A. Weldon for the Locke News, a paper published for the employees at

the Baltimore factory. Mr. Weldon, head ceramist with Locke for many years, was

associated with Fred Locke in 1918 and came to the Baltimore factory in 1921. He

was the expert at Locke in the field of porcelain manufacture.

One of Mr.

Weldon's papers gave the following history and description of the use of Seger

cones:

The Story of the Seger Pyrometric Cones

"Here we have a very interesting story of a small item which everyone

who passes through sees on or near the kiln firing sections in our plant. You

would find these same items in factories firing or vitrifying clay products the

world over, so widespread is their use."

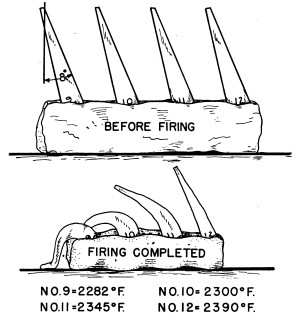

Illustrations of typical 4-cone plaques

before and after firing.

"If one cared to make a long study of systems of recording heat

characteristics, one would start back through the ages to the methods used by the early potter testing his ware from the fire. Records show

a very simple but sound early method of testing which involved placing small

pieces of the ware to be fired in the kiln and drawing them out through a small

opening in the kiln as the heat began to vitrify [the clay]. The potter would,

in some cases, study the samples for glaze action only. The writer has secured

some fine results in working with a very critical cobalt blue glaze with this

draw sample method."

"A more reliable method over all was worked out

in Germany by Dr. Herman Seger in 1886. Here you have the real beginnings of the

chemistry of the ceramic industry. The study of ceramic materials, the melting

down action, the reasons why some items melt at low temperatures and others at

very high temperatures were all worked out from this principle."

"The

use of Dr. Seger's system of pyrometric cones quickly spread over the face of the

earth as other scientific organizations took up his work. Here in the United

States General Edward Orton, Jr., stepped into the picture in 1894 and created,

at Ohio State University, the first college course in ceramic engineering

offered in this country. Simultaneously, General Orton started to manufacture

pyrometric cones."

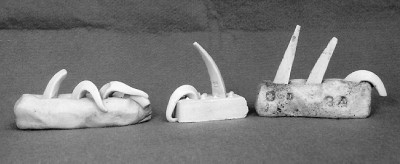

Three old sets of firing cone-plaques found in the Pittsburg dump.

Plaque on

the left has typical set of four cones (Nos. 12-11-10-9).

Center is one half of

a 4-cone plaque (Nos. 11-12).

Right is a 3-cone plaque containing an odd set of

cones (Nos. 11-10-8).

"Through application of these cones, manufacturers were able to obtain far greater uniformity of their ware regardless of

the size and kind of kiln or fuel used. Because of General Orton's great interest and devotion to the ceramic industry,

he decreed in his will that the Standard Pyrometric Cone Company should be left in trust to be operated for the benefit of ceramic research and

advancement. This company is administered by a board of trustees consisting of representatives from the Ohio State

University, the National Bureau of Standards, and the American Ceramic Society. This board maintains Fellowships at several

universities. "

"There are, in all, 61 different cone numbers in the American series. The lowest cone, No. 022, is a soda-lead

borosilicate glass and the highest cone, No. 42, is pure aluminum oxide. Within the temperature ranges used for firing gold, colors,

glazes, and ceramic products. Also, the pyrometric cone equivalent value of nearly all ceramic materials or products comes

within this range. This permits the use of cones for determining

the property called deformation temperature, or melting point."

|

"The four groups of 61 cones are:

|

|

Group No.1 - The soft series: |

Cones 022-011 |

1085 F to 1607 F |

|

Group No.2 - The low temperature

series: |

Cones 010-01 |

1634 F to 2030 F |

|

Group No. 2A - The iron-free series |

Cones 010-3 |

1634 F to 2093 F |

|

Group No.3

- The intermediate temp series: |

Cones 1-20 |

2057 F to 2768 F |

|

Group No.4 - The high temperature

series: |

Cones 23-42 |

2876 F to

3659 F |

"Here at Locke we use the No.3 series. We also have a number of other

heat-recording devices upon our kilns."

Typically, cones 9, 10, 11, and 12

are used for firing porcelain insulators. All four cones are placed in a lump of

clay at a slight angle of 8 degrees. Each cone represents the following

temperatures: No.9 = 2282F; No. 10 = 2300F; No. 11 = 2345F, and No. 12 = 2390F.

Each cone will sag when the corresponding temperature for that specific cone is

reached in the kiln. The temperature in the kiln is brought up very slowly to

maintain a uniform temperature in the kiln. When the kiln temperature finally

reaches the desired level (in some cases about 2350F), the firing is complete

and the kiln temperature is gradually lowered.

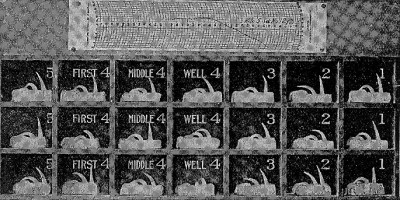

Group of 21 cone-plaques removed from a kiln

at Pittsburg High Voltage Insulator Co.

Advertisement from November 13, 1920 issue of Electrical World.

Note that the

ad says the cone-plaques "consist of three pieces".

Obviously the

person who wrote the article did not know

that each cone-plaque contained four

cones.

The Origin of the Name Porcelain:

Pottery is not porcelain. Porcelain is the

most highly organized expression of the potter's art. Porcelain is a thing

separate and distinct from pottery, because there is a fundamental difference

between the body of porcelain and the mixes or bodies of all the various sorts

of pottery and earthenware. Calling porcelain insulators "mud" is

ignoring the basic art of porcelain manufacture. Electrical wet process

porcelain is equivalent to the finest Haviland china in quality - which is

impossible to make from mud.

For those of you who have wondered where the name

porcelain came from, Mr. Weldon offers the following explanation: "The

transition period of stoneware to porcelain took place in the T'ang Dynasty

(A.D. 617-906). It was an age of splendor for all the arts in China, and the

potter's art was in no way behind the rest. From the providence of Tzu Chou the

white ware became famous throughout China and began to filter through the trade

routes, and in time found its way into Europe. In China, this ware was called

Tzu or Tzu Chou ware, or "the white ware of the north", for the city

of Tzu Chou was near Pekin. The name porcelain did not appear until much

later."

"For a number of years in Europe, fine examples of ware from

the far east were also called "Gombroom" ware, from the early English

trading post of Gombroom on the Persian Gulf, whence the Chinese porcelains were

sent into Europe. When the East India Company had obtained a concession in

Canton about 1640, the name was gradually changed to "China ware", as

it was imported into Europe. After the opening up of the sea route to China, the

first European vessel landing on Chinese shores in the year 1517, only half a

century elapsed before the Portuguese founded their first warehouse at Macao,

near Canton, in 1567."

"The Portuguese navigators of the late 15th and

16th centuries were the first to spread the ware in large quantities into Europe

and through them it began to take the name porcelain from the word "porcellana"

meaning a small bright-polished shell. This shell is found on the shores of the

Mediterranean Sea. "Porcella", diminutive of "porco", or

"pig", is derived from a supposed resemblance of the shell to a pig's

back."

|