"Threadless Corner -- The NY & ERR"

by Ray Klingensmith

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", June 1978, page 7

The story of the New York and Erie Railroad has an early beginning. In the

latter part of the eighteenth century vast areas of what is now New York,

Pennsylvania and Ohio, were wilderness. General James Clinton, a soldier and

statesman, early saw the need for a means of travel from the eastern seaboard to

Lake Erie. Clinton and General Sullivan formed a petition for Congress to act

upon, concerning the construction of a great wagon road to be built from the

Hudson River, through the southern counties of New York, to Lake Erie, but had

no luck in getting any action. Clinton never saw his "Appian Way"

built. His son, DeWitt Clinton, who in his life became associated with the

political and economic affairs of New York, had a much stronger influence than

his father had in his lifetime. He carried on his father's dream of building a

Southern Tier road. He, too, never lived long enough to make the dream a

reality.

By this time the Erie Canal had been completed through the northern

counties, and the residents of the southern counties wanted a better means of

transportation. The dream of the Clintons finally started to become reality in

1829, when a pamphlet issued by William C. Redfield proposed a railroad rather

than a wagon road. In 1831 the first trainload of passengers ever drawn by a

locomotive took place in South Carolina. At the beginning of 1832 there were

only 44 miles of railroad in operation in New York, so the idea of a line

hundreds of miles long didn't catch on instantly. A survey for the NY & ERR

route was made in 1834. The original proposed route started on the Hudson River,

progressed through Goshen, with a population at that time of 500, to Monticello,

Deposit, Binghampton, Owego, to what is now Corning. At that time Corning was

still a vast forest. Westward the proposed route continued through the

Allegheny Mountains, until it split near Lake Erie, with two possible

terminations, Dunkirk and Portland.

In the years to follow many obstacles got in

the way, mainly financial barriers, and many changes were made in the route.

First ground breaking for the New York and Erie Railroad took place on November 7, 1835, near Deposit, Delaware County, New York. Finally, on September

23, 1841, a small section of line between the Hudson River and Goshen was

completed. Grading was taking place at that time at various points along the

line. Iron rails were shipped to Dunkirk on Lake Erie in 1842, to be laid to a

point six miles east of Dunkirk, where a stone quarry supplied stone for

construction. Work continued, and in June of 1843 the line was completed

westward to Middletown, to Port Jervis in January 1848, to Binghampton in

January 1849, to Owego in June 1849, and to Elmira in 1850. A branch line to

Newburg was opened in 1850. Newburg was among those involved in the early dispute concerning the location of the eastern terminus. Piermont was decided upon,

and the residents of Newburg demanded a branch line, thus a branch line was

completed from the main line to Newburg.

Many confrontations took place in this

period of construction. One interesting case was the confrontation of a change

of route between Port Jervis and Binghampton. With the change made, a small

portion of the line would have to be constructed in Pennsylvania.

With agreements drawn up with the State of Pennsylvania, the NY& ERR

Company later found itself in a position of meeting heavy demands of residents

living in a few small Pennsylvania communities. The railroad was forced to

either meet these demands or change the route back into New York, where

mountainous conditions would delay completion to Binghampton. If completion was

delayed too long, the charter would have been lost, so the railroad met the

large demands of its neighboring state.

Finally, after years of struggle, in May of 1851, the entire line was

completed from Piermont, on the Hudson, to Dunkirk, on Lake Erie. Although the

rails didn't join with the populous New York City, a ferry went from that city

to Piermont, where a large pier had been built by the railroad company to

receive passengers and freight for westward transportation. At the time of

completion, the New York and Erie Railroad was the longest railroad in the

world. On May 14-17, 1851, two excursion trains traveled the entire length of

the line. Passengers on the excursion included the President of the United

States, Millard Fillmore; the Secretary of State, Daniel Webster; Attorney

General John Crittenden; many railroad officials and various politicians. The

occasion was a joyous one, with thousands of people gathering in the small towns

along the route, cheering as the excursion trains entered the towns. Banners

waved, cannons roared, and many a speaker became hoarse after two days of giving

a speech at each of the stopping points. On May 15th the trains reached Dunkirk,

where a large festivity took place. I would very much like to go into more

detail concerning this occasion and the construction period but limited space

prohibits too much detail.

The New York & Erie was plagued with financial difficulties from its very

beginning. For years after the completion of the line in 1851, many expenditures

kept the company from really getting on its feet. Partially to blame was severe

damage to the line in January and February of 1857 by heavy flooding. There also

was the problem of lost revenue due to a rate of passenger fare war between the

NY&E and the New York Central Railroad. Also, the NY&E had built its

rails with a six foot gauge, which created many problems for the line, due to

the fact that adjoining lines made use of the standard 4' 8-1/2" gauge.

Passengers wanting to travel on another railroad connecting A with the NY&E

had to wait for their merchandise to be transferred from the NY& E cars to

the cars of the standard gauge line. Had the NY & E been a standard gauge

line, the cars could have continued on without interruption. After a

reorganization in April, 1861, a new company was formed, the Erie Railway

Company, and the New York & Erie Railroad ceased to exist.

To save confusion, at this time I would like to point out that there was also

a New York and Erie Telegraph Company which was constructing a telegraph line on

the wagon roads of southern New York state. It was built by Ezra Cornell.

Although the names are the same, they were in no way related. However, Charles

Minot, superintendent of the railroad company, was aware of the telegraph line

being built, and he suggested to the directors of the railroad to build a

telegraph line parallel to the NY& ERR tracks, on the railroad property. The

directors initially felt the benefit derived from the telegraph line would not

be worth the cost of construction and maintenance; but Minot finally succeeded

in convincing them to build such a telegraph line. By the end of 1850 the

railroad telegraph line was completed between Piermont (on the Hudson) and

Goshen, but was not in operation yet. West of Goshen, portions of the line were

up, but there were many gaps to be filled before a complete telegraphic link

could be made the entire length of the railroad. In December, 1850, Minot hired

D. H. Conklin to test the line between Piermont and Goshen. On January 4, 1851,

the wire was tested and found to be in working order. In the winter of 1851 the

line was completed to Port Jervis. By spring of 1851 the line was complete as

far west as Susquehana Depot.

It was in those early days that passengers, baggage, and freight were

transferred from the railroad piers at Piermont onto steamboats each day. Every

day the train brought in a different amount of cattle to be transported to New

York City. For that reason, much of the loading activities at the pier were

postponed until the train arrived. This was because enough room had to be left

for all the livestock on the boats, and no one knew how much livestock was to

arrive. This caused considerable delay. Operator Conklin, realizing the delay,

arranged with the conductor of the stock train to send a telegram to Piermont

with the information concerning the number of cattle to arrive. This act

quickened the loading procedure, and was the first practical use of the

telegraph for railroad business in this country.

In the early part of 1851 the entire telegraph line was completed. The

telegraph line was placed under two superintendents. L. G. Tillotson was

superintendent for the line between Owego and New York, and Charles L. Chapin

between Owego and Dunkirk. At that time Tillotson was only 19 years old, but he

was well educated in the art of telegraphy.

The first use of the telegraph in this country on a railroad for the movement

of trains took place in the autumn of 1851. Until that time a "time

interval system" was used. Under that system, certain trains had priority

over trains moving in the opposite direction. When a train was delayed, the

entire timetable became a mass confusion, and there was danger of head-on

collisions. On that particular autumn day in 1851, Superintendent Minot was

riding a westbound express train. An eastbound train was late in arriving at a

station, so Minot decided to give the telegraph a test. The following is an

account of the event as told in the book, The Story of the Erie, by

Mott:

| The train, under the rule existing, was to wait for an

eastbound express to pass it at Turner's, 47 miles from New York. That

train had not arrived, and the westbound train would be unable to

proceed until an hour had expired, unless the tardy eastbound train

arrived at Turner's within that time. There was a telegraph office at

Turner's, and Superintendent Minot telegraphed to the operator at

Goshen, fourteen miles further on, and asked him whether the eastbound

train had left the station. The reply was that the train had not yet

arrived at Goshen, showing that it was much behind its time. Then,

according to the narrative of the late W. H. Stewart, given to the

author in 1896, Superintendent Minot telegraphed as follows, as nearly

as Stewart could recollect:

To: Agent and Operator at Goshen:

Hold the train for further orders.

Chas. Minot, Superintendent

He then wrote this order, and handed it to Conductor Stewart:

To Conductor and Engineer, Day Express:

Run to Goshen regardless of opposing train.

Chas. Minot, Superintendent

"I took the order", said Mr. Stewart, relating the

incident, "showed it to the engineer, Isaac Lewis, and told him to

go ahead. The surprised engineer read the order, and, handing it back to

me, exclaimed:

"Do you take me for a d--n fool? I won't run by that

thing!"

"I reported to the Superintendent, who went forward and used his

verbal authority on the engineer, but without effect. Minot climbed on

the engine and took charge of it himself. Engineer Lewis jumped off and

got in the rear seat of the rear car. The Superintendent ran the train

to Goshen. The eastbound train had not yet reached that station. He

telegraphed to Middletown. The train had not arrived there. The

westbound train was run on a similar order to Middletown, and from there

to Port Jervis, where it entered the yard from the east as the other

train came into it from the west."

An hour and more in time had been saved to the west-bound train; and

the question of running trains on the Erie by telegraph was at once and

forever settled. |

So, with the telegraph line in working order, we come to the next part of the

story -- line insulation.

There is an insulator embossed N.Y.&.E.R.R. This is the CD 736. I've

tried to pinpoint an exact date on the manufacture of these, but so far have not

confirmed anything. The first wire was completely up in 1851. By what I've

gathered, there was another wire put up in 1856 or 1857. Where the CD 736

NY&ERR fits in is a good question. In the book, The Story of the Erie,

Mott states that Mr. Cornell supplied insulators for the first railroad

telegraph line. "These were of brimstone, enclosed in iron pots, and of

small value." In the book, Wiring A Continent, by Robert Thompson,

it is stated that the New York and Erie Telegraph Company (along the

wagon roads) also made use of these insulators. They were in use on that line in

the late 1840's, and the line didn't work well until they were removed from it. I

think that if the brimstone insulators were used on the NY&E Tel. Co.

lines and were found unsatisfactory, then the NY& ERR wouldn't attempt using

the same faulty type of insulation two or three years later. I think

somewhere in the recording of the facts concerning insulation on the railroad,

an error was made by confusing that line with the NY&E Telegraph

Company line of a couple years earlier. So, the first insulators used on the

railroad may have been the CD 736 NY&ERR. It's also possible the CD 736's

replaced the brimstone units in 1852 or in any year to follow, if the brimstone

units were in fact used.

The railroad was in poor financial condition by 1857, and the name was

changed to the Erie Railway Company (ERW) in 1861; so the CD 736 NY & ERR

units were more than likely produced between 1849 and 1857. That would date them

as being perhaps the oldest embossed threadless. There were also several other

different threadless units used on the line, including various color and size

variations of the unembossed CD 736, the CD 736 with a J on the dome, and the CD

729 J. S. Keeling. The CD 736 NY&ERR items come in at least two different

variations. (see figs. 1-3 on page following) Some units are embossed on the

front skirt: N.Y.&.E.R.R. (In the future this will be called variant one.)

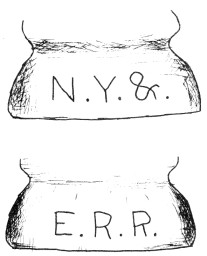

Fig. 1. The CD 736 NY&ERR, variant #1. Embossing on front skirt. |

Figs. 2 & 3. Variant #2. NY& on front skirt, ERR on back

skirt. |

Other units (variant two) are marked on the front skirt: N.Y.&.; and on

the back skirt: E.R.R. The latter variation seems to be the scarcer of the two.

Variant one has been found in aqua. These are very crudely made, and minor

traces of milky swirls and olive streaks usually appear in the glass. Variant

two is also found in the same shade of aqua with similar characteristics. It

also comes in a color described as a darker green-gray color of glass. This is a

definite color variation. I've also been told by at least three collectors, they

had seen a NY&ERR in puce! To those of you who have not seen a glass

article in puce, let me say it's hard to describe. The easy way out would be to

call it a reddish color. Seeing one of these in dark puce would certainly make a

few heads shake in disbelief! I'm not certain which type of embossing this one

had. I understand there was one of these found, along with the small fraction of

another.

Gerald and Esta Brown have informed me that when the old depot at Goshen, New

York, was torn down several years ago, a box was found in the building that

contained at least five NY& ERR's, two or three ERW's, and one tall hat. I

believe all those NY& ERR's were the variant one type. These were more than

likely some of the first NY & ERR's to enter the collecting scene; and those

original five make up a large part of those in existence today. There aren't

many of them around. As with all other rare insulators, certainly many of them

were made, but not many have survived the elements. I consider the CD 736

NY& ERR to be among the most desirable of all threadless. They are an

interesting hat style, are very rare, have a wealth of information and history

behind them, and were a part of what was, in my opinion, the greatest work of

railroad achievement.

A real big thanks must go out to Gerald and Esta Brown, who so kindly loaned

to me the book The Story of the Erie. That book was of unmeasurable

assistance in writing this article, and I feel very honored in being trusted

with such a rare and valuable book. A big thanks to Bob Pierce for loaning me

his copy of Wiring A Continent, which was of help in this article and

which will be responsible for a large part of many future articles; and to Dick

Bowman and Dieline Coleman for information on color variations.

Next month -- the "1867 George Floyd" threadless.

If anyone has any info to share, please drop me a line at 709 Rt. 322, East

Orwell, Ohio 44033. It's you folks out there in collectors-land that make this

article possible each month.

|