Brookfield Goes To War

by Larry Larned

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", August 1990, page 10

At 1:30 p.m. August 7, 1917 the troop ship Antilles formerly a South Atlantic

banana boat left a pier in Hoboken, New Jersey, and started down the Hudson

River. On board the Antilles was the First Telegraph Battalion, Signal Reserve

Corps headed for Europe to join the A.E.F. (American Expeditionary Force)

fighting W.W.1. in France. The troops aboard the "Antilles" were

ordered to remain below deck to avoid being seen by German agents operating in

the New York City area. A short trip brought the 'Antilles" to the rendezvous,

Gravessend Bay, to form the convoy; troop ships and freighters alike. The

freighters carried munitions and enough material to build about 200 miles of

open wire telephone line. Meanwhile, just 30 miles away the Brookfield Glass

Company in Old Bridge, New Jersey, was operating full blast making insulators

for the war effort from specifications provided by the various governments and

companies that ordered them. During these times everybody was doing whatever

they could to enhance the patriotic spirit. Frank Brookfield, who was Vice

President and Sales Manager of Brookfield Glass Company joined the army and

shipped overseas to France. The task of managing the Brookfield Glass Company

and filling war related orders was left to Henry Brookfield, President and Plant

Manager. As a gesture of patriotic good will, Henry Brookfield ran the plant at

near cost, taking as little profit as he could.

First Telegraph Battalion, Bell of Pennsylvania, in front

of Independence

Hall, Philadelphia, June 18, 1917

During May, 1917 at conferences held in Washington, D.C, and at the direction

of Major General John J. Pershing, Colonel Edgar Russel of the U.S. Signal Corps

met with Major John J. Carty, Signal Officer Reserve Corps, regarding the best

form of telephone and telegraph system for long lines in France. Major Carty, as

chief engineer of AT&T, had been in charge of the engineering team which had

built the transcontinental toll line from New York to San Francisco during 1915.

The "400 Mile Line" Chaumont -- Tours

(Courtesy of AT&T Archives)

The problem presented by Colonel Russel was the construction of an American

telephone and telegraph line 400 miles long extending from the west coast of

France and across that country "to some point not given, and to construct

this line so that it might fit into an ultimate telephone and telegraph system

extending to distances and places in the British Islands and on the continent of

Europe at that time unknown." So much of the philosophy! As it turned out

the famed "400 hundred mile line" was constructed across France

beginning at St. Nazaire on the coast and extending inland generally through the

towns of Nauntes, Angers, Tours, Bourges, Nevers, Beaune, Dijon, Langres,

Chaumont and Neufchateau often passing through open country.

Design work for the

line was initiated and took place in the United States following a field survey

in France during June, 1917 by Captain Paddock, Lieutenant Repp (the man who

invented the "Repp Insulator" -- subject of a future C.J. article) and

Lieutenant Glaspey. During the summer and fall of 1917 Lieutenant C. L. Howk

formerly of Western Electric made a study of telephone requirements needed to

serve American troops in France. His study revealed a much more extensive system

would be needed (the camel's nose was now under the tent!) and a memorandum was

prepared and sent to Washington.

Orders were changed to include a "265 mile

line", to branch off the "400 mile line" just behind the front

lines of battle. Further orders to expand the system were received following the

discovery that the French system was overloaded and in many areas of France in a

state of disrepair. Suddenly the U.S. Signal Corps was faced with a huge

undertaking. The war had been raging since 1914 almost three years before the

U.S. became involved. France had made the mistake of sending its civilian

communications men off to war disregarding the need to maintain the government

operated Department of Postes et Telephones, and Telegraphs. And the

availability of communications supplies needed to repair the French lines was

practically nonexistent.

Faced with all of these concerns, the U.S. Signal Corps

turned to AT&T for help. Patriotic fever was running high when 25 constructing

and operating telegraph battalions were made up of volunteers

organized from the various Bell System companies throughout the U.S. They

received military training and were nicknamed "Bell's Battalions".

Bearing the colors of their respective Bell System Companies, they numbered

25,000 employees. Included were 213 women operators who staffed the 273

telephone exchanges built in France by American troops. The president of

AT&T, Theodore N. Vail, saw each unit off to war and at each farewell,

provided hampers of food from his Vermont farm.

Two of Bell's Battalions

remained in the U.S., one at Western Electric's Hawthorne Works in Chicago and

the other in Western's New York engineering office. Each contributed to laying

out the famed "400 mile line".

As anyone who has served in the armed

forces knows, and I had my experience, the planning phases of military

operations are the most confusing and often counter productive. The "400

mile line" was no exception. About August 1, 1917 the engineering

department was directed to proceed with the manufacture and shipment of

telephone and telegraph equipment for the "400 mile line". This

included two repeater stations, two test boards and a quadruple duplex multiple printer. The equipment was manufactured and shipped from Chicago to New

York where it was crated for shipment to Europe. On August 25, 1917 further

orders were received to include eight 100 line battery switchboards and five 100

line local battery switchboards. These were shipped to New York and also crated.

Then on December 1, 1917 revised plans for the "400 mile line" were

received which called for a complete revision of former designs. All of the

equipment was sent back to Chicago, uncrated, rebuilt, recrated and set back to

New York!

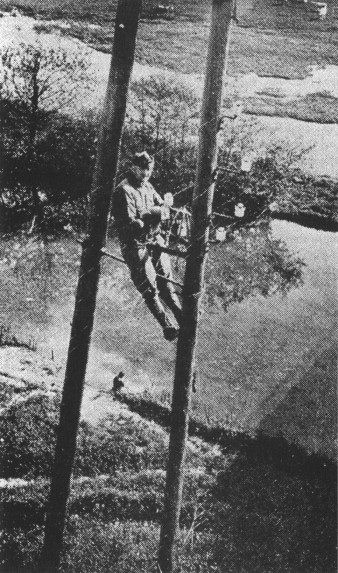

Meanwhile pole construction on the "400 mile line" had begun between

Chaumont and Tours, this being the first American line built in France. Interestingly enough my uncle, Lt. Elmore Smith, who

led an engineer company in France and later became the U.S. military attaché to

Chiang Kai-Shek on Formosa, was placed in charge of procuring poles for the

Signal Corps. The decision to use native poles was made to save the tonnage

required for transportation to Europe. Since telephone repeaters were used on

the line, a smaller gauge wire (104 mils) was strung. This became standard for

all open wire long lines built by the Signal Corps in France.

The "400 mile

line" used American 10-pin cross-arms and CD 145 insulators. It's a safe

bet that they were Brookfield insulators since Brookfield Glass Company,

according to William L. Brookfield, was providing 50% of its production to

Western Electric at this time. And with the exception of poles, Western Electric

provided all of the materials for constructing the "400 miles line",

including 4,000 miles of wire, 14,000 cross arms and 140,000 insulators. While

the "400 mile line" was under construction in France, disaster struck

the Brookfield plant in Old Bridge on February 10, 1918 when 28 freight cars

were destroyed. The disaster is best told in William Brookfield's words,

"One of the worst things that happened during WWI was that Father (Henry M.

Brookfield) had an enormous order of insulators finished, waiting for the engines

to take them to the wharf. Saboteurs set the sidings and packing room as well as

the warehouse on fire and burned the whole shipment."

Was the shipment

headed for France? And did it contain CD 640 "gingerbread men" ordered

by the French government to be used on the decimated French telephone lines? The

answer to the first question is a definite yes. The reference to the

"wharf" is very interesting. The Brookfield plant was served by a railroad

siding which led to a large docking facility in South Amboy, New Jersey, on

Raritan Bay. During World War I the old Bridge - Morgan area was the site of munitions plants where 60% of all shells used by American forces were loaded

with TNT, placed in freight cars and taken to the dock in South Amboy. The dock

or wharf was served by lighters which took war materials to Sandy Hook where

they were loaded on ships bound for France. And the son of the man who was in

charge of the siding remembers his dad remarking that "the public was led

to believe... that the box cars were thought to have carried shells but people

would be surprised at what was in those box cars."

Apparently, the

saboteurs were aware that Brookfield was producing insulators for shipment to

France and this order in particular was targeted by German agents. Since

Brookfield was producing insulators for various foreign governments, France

certainly was one of them and the CD 640 somehow played a role. But what role?

When American troops arrived in France, the U.S. Army leased communication lines

from the French. These lines were "strung on metal brackets".

Eventually the U.S. Army Signal Corps maintained and operated 12,333 miles of

wire leased from the French. The leased system covered almost the whole of

France and reached from LeHavre on the north, with connections to England, to

Bordeaux and Marseille on the south, to Brest and St. Nazaire on the west, and

to Chaumont and Neufchateau and the zone of the armies on the east. The extent

of the leased system was not originally anticipated and contained in the Report

of the Chief Signal Officer is the following excerpt, "Owing to the

frequent shortage of materials, an important part of the work consisted of

engineering substitute arrangements... as a basis of request sent to the United

States." But standard American insulators were not suitable for French

lines! Their lines were attached to insulators cemented to small diameter pins

projecting from metal brackets. At first, the U.S. Signal Corps placed 10 pin

cross arms on the French poles using American CD 152 insulators. But as time

wore on the Signal Corps maintained leased lines using brackets. A signal Corps

photo shows white U-2051, the gingerbread man design in porcelain -- being

installed by the U.S. Army on brackets between Neufchateau and Vancouleurs.

Leased line on the road from Brest to Pontanazen

showing French construction

above American construction below.

(Courtesy of the U.S. Signal Corps)

U-2051's on brackets being installed between Neufchateau and Vancouleurs

(Courtesy of the U.S. Signal Corps)

The

use of brackets vs. crossarms became a big issue between the U.S. Army and the French Postes et Telephones and Telegraphs. French construction in

ordinary times did not permit cross arms along the highways. They were

considered pas jolie, and in addition, the French believed that their soil was not

sufficiently solid to hold single poles with cross arms. But the most important

reason of all for the opposition to cross arms came from the fact that their use

would require either that the lines be moved and placed on private property or

else so close to the trees bordering the highways that extensive trimming would

be required.

It was difficult to decide whether the suggestion of trimming trees

or of placing poles on private property caused the greater uproar among the

French officials. Negotiations followed, attended by the then Captain Voris,

Signal Officer of the First Division, who later became Signal Officer of the

First Army Corps. The French were very specific in ordering that the leased

lines be located between the edge of pavement and the rows of trees -- requiring

brackets. Until this conflict could be resolved it appeared the U.S. Army Signal

Corps would be using brackets for new work along the French highways.

My strong

suspicion is that the U.S. Army ordered a prototype French style CD 640 design

in glass from Western Electric. Western Electric in turn ordered the prototype

from Brookfield. Brookfield designed a pattern, created a mold and produced an

untold number of the CD 640 style using the standard U.S. 4 per inch threads

with a scaled down pinhole diameter. After all, these would be cemented on small

diameter pin brackets rather than screwed onto standard American pins.

Somewhere, sometime a metal bracket will be found on which David Wiecek's crown

portion and Bob McElvaney's one arm and outer skirt portion will fit. (See Crown

Jewels of the Wire, April, 1989)

Meanwhile as negotiations continued for

maintaining and operating leased lines, the U.S. Army set a policy for locating

newly constructed long lines. It became Army policy to conform with the French

in construction as far as practicable. In cities and towns the wires of the

French lines were carried almost wholly on the tops of the houses with steel

fixtures. This was not possible with the American cross arm type of

construction, and towns were detoured with open wire lines running through open

country but as close to roads as possible. Where warranted, S points or junction

poles were established and CD 196 insulators were used, most probably Brookfield

"B's.

Captain Voris was very determined that it was unwise to consider

building or rebuilding leased lines between the trees and the edge of roads

because he felt sure that main roads would handle a great deal of military

traffic and there would be constant danger of breaking poles. His opinion

prevailed. As it turned out, wherever it was necessary to place any poles on

private property the formal consent of the property owners had to be obtained

and the U.S. Army used ten pin, six pin and brackets requiring a variety of

insulator styles.

Photographs taken by the U.S. Army show CD 112's, 145's, 152's, 196's and porcelain

U-2051's. The glass CD 640 style isn't visible. Until

one is found in French we can assume that none ever made it across the Atlantic.

Most, if not all were destroyed on that fateful day of February 10, 1918.

S points or junction poles using CD 196's on branch

to Beaumont Barracks and Nevens, Tours France.

(Courtesy of U.S. Signal Corps)

While

the war was raging in Europe during the winter of 1917-1918, Henry Brookfield was

worried. He had applied to the government for a coal priority to keep his glass

furnaces operating. By the time he received the priority -- it was too late --

he had run out of coal and the furnaces were cold. Few insulators were made at

Brookfield during early 1918 and once the furnaces were started again they

were operated only until the middle of June when the annual shutdown of the

Brookfield plant took place. The shutdown period each summer allowed for furnace

maintenance. This was necessary because the furnaces were so hot that they had

to be blown out from the middle of June to the beginning of September. In all,

half a year of production was lost between the lack of coal and the necessity for furnace maintenance.

Right of Way Permit which had to be obtained by the U.S. Army of

property

owners. This one is stamped by the "Mairie" (mayor of the town).

Also shown is

the form used to report daily construction and material used.

Just two weeks after

resuming insulator production the Brookfield plant was struck by catastrophe

again -- this time on October 4, 1918.

The evening papers on October 4, 1918,

reflected the fact that American doughboys had broken through the German lines

in France. As the millions of people in the New York-New Jersey metropolitan

area were finishing supper they heard a dull rumble like distant thunder. Before

the night was over all of New Jersey and New York City heard the roars of

exploding shells. The Thomas Gillespie shell-loading plant at Morgan (Old

Bridge) was being blown to the sky -- the result of sabotage. The explosion, 71

years ago last October, was one of the largest and most devastating man-made

disasters in American history. And the Brookfield Glass Company, a neighbor of

the Gillespie shell loading plant, was severely damaged. All of the windows were

smashed and Brookfield shut down again due to the devastation in the area. The

magnitude of the explosion was tremendous as 31,000,000 pounds of explosives

including 1,200,000 shells and 12,000,000 pounds of TNT destroyed the 700 wooden

buildings belonging to Brookfield's neighbor. The blast shut down the subways in

New York City and broke windows in Brooklyn. The Gillespie plant was turning out

32,000 artillery shells a day making it the largest of the four major munitions

plants in America. Truly, the war had been brought home to the Brookfield Glass

Company.

Just 39 days later the guns on the western front fell silent and

further work on building 59 signal corps projects involving the string of 7500 miles of wire

was cancelled. Many leased lines were returned to the French and 83 Signal Corps

installations were dismantled. Miles and miles of open wire lines were also

dismantled.

During a remarkable period of 11 months "Bell's Battalions' had

erected 1,724 miles of permanent pole line, and had strung 21,000 miles of wire.

Almost 2,000 miles of wire had been strung on French pole lines making a total

of 23,000 miles. A line from Rochefort to Talmont, with a cable crossing the

Garonne River, was constructed for use by the U.S. Navy. Taken altogether, this

was equivalent to building a pole line with one 10-pin cross arm from

Washington, D.C. to San Antonio, Texas, and with an additional cross arm and 10

additional wires from Washington, D.C. to Atlanta, Georgia.

Conditions changed

so rapidly, with the movement of the front line, that it was often difficult to

plan the location of communication lines. A pole line had been planned from

Joinville, north of Chaomont to Compiegne, but before any of the material could

be distributed, most of the area was in the hands of the enemy. Later, a line

using this same material was built from Chaumont to La Belle Epine, southwest of

Paris.

| |

A.E.F. Telegraph Circuit Chart, November 11, 1918

After the armistice, a somewhat different telephone and telegraph system

emerged in Europe. This was for the American Relief Administration under Herbert

Hoover and it continued to function for many months but further construction

using American standards had ceased.

The Brookfield Glass Company never fully

recovered from the effect of WWI and it ceased operations during 1922 with a

legacy of helping to assure victory in France but defeated by sabotage in the

U.S.

Special thanks to the following who helped with the research for "Brookfield

Goes to War", Alvia D. Martin, Curator, Madison Township Historical

Society; William L. Brookfield, oldest son of Henry Brookfield; Bunny White,

AT&T Bell Labs; the U.S. Army Signal Corps; the National Archives; and to

Vickie Crafa who diligently typed and arranged the text.

|