Patent Office

by Elton Gish

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", October 1992, page 18

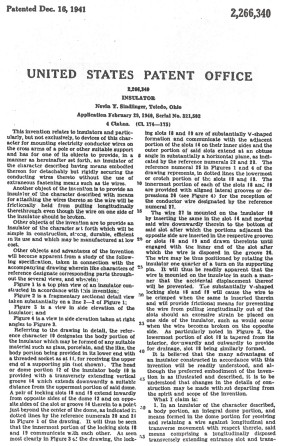

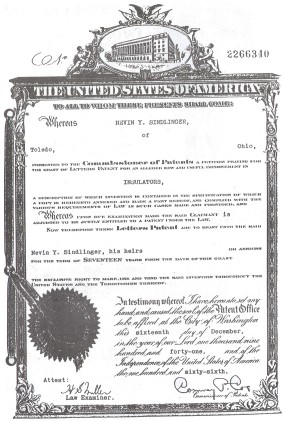

NEVIN Y. SINDLINGER

SELF-TYING INSULATOR PATENT

Jack Snyder tracked down Mr. Sindlinger's family in his home town of Toledo,

Ohio way back in 1974 after he saw a copy of the Sindlinger patent drawing on the

cover of the July, 1974 issue of Crown Jewels. Jack interviewed Mr.

Sindlinger's wife and daughter who showed him two pottery models and documentation, and they allowed him to make a couple of

photographs. In the

July, 1984 issue of CJ, Jack published the information from that interview and

the two photographs that he made of the two pottery models. Finally, in 1991,

Jack's dream came true when he purchased the two pottery insulator models from

Mrs. Sindlinger along with the documentation. He very generously mailed

one of the models to me so I could inspect it, make ink drawings, and take a few

photographs. I was amazed at how small the model was as you could easily wrap

your whole hand around it. It is rare indeed that family members of a patentee

remain that can relate some of the facts behind the patent. Thanks to Jack's

efforts, we have a more complete record of the events surrounding this unusual

patent.

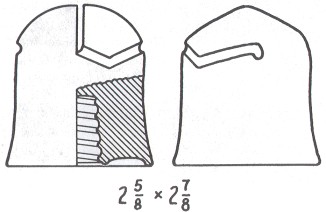

Below are the ink drawings that I made. We will not assign a U-number to

this design since only pottery models exist, no commercial production was

ever made, and the original intent was to make them of glass.

Nevin Y. Sindlinger lived in Toledo, Ohio where he worked for the Wheeling

and Lake Erie Railroad as a combination electrician and signalman. Mr.

Sindlinger was well aware of the effort required to secure the signal wire to an

insulator by means of a tie-wire. He thought that there must be an easier way,

and, to that end, he set out to develop an insulator design to make his job

easier by eliminating the need for a tie-wire. Mr. Sindlinger was a constant

tinkerer, so it was natural for him to set out to solve this problem. He sought

the advice of fellow workers and others, and, after two years of

trial-and-error, applied for a patent on February 29, 1940 detailing the design

of a self-tying twist lock insulator. Mr. Sindlinger was granted patent

2,266,340 on December 16, 1941. A copy of the patent grant and the patent are at

the end of this article.

Mr. Sindlinger was not the first person to seek a way

to eliminate the need for tie-wires. Indeed, he must have been the last person

to do so since he was granted the last patent for a self-tying insulator. There

have been about 130 patents granted for self-tying designs, but only a handful

were put into production. Many of the self-tying patents are quite unique and

complicated which either required impossible manufacturing techniques, or they

were simply too expensive to produce. It seemed that everyone had an idea for a

"better mousetrap", but few of the patents were practical. The bulk of

the patents for self-tying insulators were granted from 1902 to 1920.

Only

eleven self-tying insulator patents were known to have been produced as

represented by extant specimens:

U-182A/B (Prenzel,1885)

CD 141.8 (Buzby, 1890)

CD 158.9 (Hauty, 1893)

CD 207 (Renault, 1900)

* U-184 & CD 206.5 (Harloe, 1902)

U-181 (Bell,1903)

CD 141.7 (Twiggs, 1905)

* U-185 (Slusser, 1908)

* U-183

(Ranson, 1909)

U-187 (Pierce, 1910) *

U-186(Purkey,1914)

Four of these patents

(marked with "*" above) were either twist-lock styles or the wire was

slightly bent by twisting the insulator back and forth to align the wire with

the projections. The classic example of this later operation is the Harloe

patent.

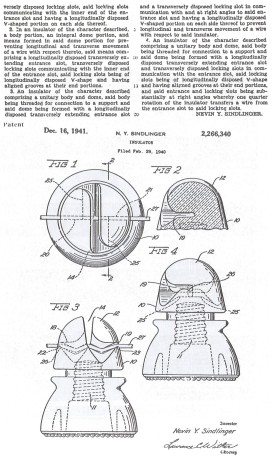

The Sindlinger twist-lock design appears to be stronger and less prone

to breaking than the fragile looking projections found on U-183, U-184 and

U-185. After first unscrewing the Sindlinger insulator 1/4 turn, the line wire

was then placed in the vertical slot which was formed all the way through the

top of the insulator. Then, by twisting the insulator (screwing it back down on

the pin), the line wire becomes slightly bent by the two downward pointed top

edges halfway along the two lateral grooves. The wire would then be guided

upward by the sloped groove until it fell into the small slot or notch at the

end of each groove. Thus, the line wire was snapped into its final resting and

held securely by the two notches on either side of the insulator, and by the two bent sections of wire. Jack tried this with

a piece of wire and happily reports that the pottery model works perfectly! The

wire actually snapped into the small notch and it was held firmly in place!

I

would guess that the Sindlinger patent was one of the best self-tying designs

since the line wire was slightly bent in two places to firmly secure it against

horizontal movement, and the two deep grooves with a downward notch at the end

would keep the insulator from unscrewing on the pin once the line wire was

snapped into place. However, I doubt that this design could have been mass

produced due to the intricate, deep cuts into the crown.

Mr. Sindlinger's patent

was granted 10 years after the last self-tying patent -- an idea 30 years too

late. In the heyday of self-tying designs, the few styles actually produced met

with very limited success, and they are very uncommon to unique in insulator

collections. So, his idea surely was met with little interest by insulator

manufacturers. His bad timing was further complicated by the fact that the U. S.

was forced into World War II just nine days earlier. Money and material was not

available for investment in anything but the war effort.

Mr. Sindlinger's wife

had second thoughts about her husband spending so much money on a foolish idea.

Upwards of $100 was spent just on patent fees, applications, etc., which was a

sizeable sum in 1940 for most families. Many times that amount was probably

spent on developing the idea, blueprints; patent attorney fees, and making the

pottery models. Due to lack of money, the two patent models were made by hand in

his workshop. The threaded pin hole is very crude and too small to fit on a

standard pin. He may have used a wooden pin to form the threads, but did not

realize that the clay would shrink after firing. According to Mr. Sindlinger's

daughter, the models had to be fired at an unknown facility in New Philadelphia,

Ohio. Note that the blueprint more closely resembles the pottery models than

does the patent drawing.

The original idea involved a glass insulator. The

patent drawing even resembles a Hemingray CD 208 or CD 213. Mr. Sindlinger

approached Western Electric to see if they would be interested, but they

referred him to Hemingray. Nothing ever came of the correspondence with

Hemingray. The design was probably too costly to produce from glass and

prohibitively complicated, too, for porcelain since costly glazewelding

techniques had not been used for more than 20 years (U-186 required making it in

three separate pieces and fusing them together with glaze). Hemingray 42's could

be turned out by the millions in short order, and labor to add tie-wires was

cheap. All of the years of effort spent developing this idea were wasted. The

two pottery models are all that remain of one man's dream.

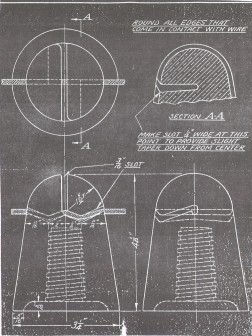

Below are six photographs that show all of the details of one or the pottery

models from every conceivable angle.

Medium Image (186 Kb)

Large Image (411 Kb)

Medium Image (132 Kb)

Large Image (296 Kb)

Medium Image (105 Kb)

Large Image (246 Kb)

Medium Image (192 Kb)

Large Image (292 Kb)

|