Frederick Newton Gisborne, 1824-1892

by Eric Halpin

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", December 1991, page 10

The somewhat plain, white and moderate in size, porcelain insulator U-1135

bears the dome incuse words "Gisborne Pattern." Such a humble insulator

belies the significance of the great man of enterprise and energy who designed

it.

Born into a well to do family in England, Frederick Gisborne was extensively

schooled and excelled in mathematics, botany and civil engineering. His

ancestor, Sir Isaac Newton, would have been proud of the young man's scholastic

achievements, but books and formal studies could not hold Frederick's attention

forever. In 1842, at the age of 18, he undertook a three and one-half year

around the world journey to further advance his understanding of the many areas

of interest that swirled in his mind. But eventually the rugged demands of world

travel took its cost and Frederick settled down, for a period, to farm in the

Province of Quebec.

By 1847 Frederick had graduated with honors from the first

Canadian school for telegraphers and was quickly hired by the recently formed

Montreal Telegraph Company. His knowledge of the workings of the telegraph soon

propelled him to head the main exchange in Quebec. The rapidly expanding

telegraph industry was always on the lookout for new talent and so it was

natural that Gisborne came to people's attention. The "British

North-American Telegraph Association" lured Gisborne away with a position of general manager. His

mandate was to promote the establishment of connecting lines from the Maritime

Provinces with the rest of Canada and the United States. Under his personal

direction, lines were established east from Quebec City towards the Province of

New Brunswick and from Halifax, Nova Scotia west towards New Brunswick.

From

1849-1851 as superintendent and chief operator of all government lines in Nova

Scotia, the serenity of married life and his dormant wanderlust for travel

battled. Taking a leave of absence, he moved to the Island of Newfoundland and

with governmental assistance began to explore the uncharted interior, scouting

for a suitable path for a planned telegraph line to run from St. Johns to Cape

Ray. The topography was brutal, alternating between bogs and marshes to sheer

2,000 foot, heavily fractured tectonic plates forming impenetrable valleys.

Chunks of inner earth littered the wind swept barrens. None of the six man

exploratory work party could complete the initial 400 mile trip except Gisborne

himself and it was three months before he completed the survey at a mere cost of

$2,000.

The task of completing the Newfoundland line was so demanding on his

time that Gisborne resigned from the Nova Scotia telegraph and worked on the

"Newfie" line full time. However, even the optimistic Gisborne was

unprepared for the tribulations to complete this line. Before long this

telegraph project had bankrupted Gisborne and he had to relinquish much of his

control in 1854 to his new-found and moneyed partner, Cyrus Field, of Atlantic

cable fame. This reversal of business fortunes, compounded by the sudden passing

of his wife would have laid most men down for the count. Yet, by the end of

1856, not only had he finished this telegraph line with the aid of his partners

but had laid the first under water line on this side of the Atlantic, between

Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. He realized his dream of extending the

line all the way to England was out of his reach due to a lack of the massive

financial backing that such a project would require. Now Gisborne sought out new

conquests for his seemingly never dry reserve of energy and ideas.

Always an

inventor at heart, Gisborne developed a system for paying out line during

underwater construction and an insulation that resisted salt water. He also

designed a chisel-scoop post hole digger which was acclaimed throughout North

America. Other inventions included a flag and ball semaphore signal for ships,

an electric recording target, an anti-induction cable and improvements to gas

illumination devices. Numerous international scientific awards were presented to

Gisborne for his achievements and telephony. But books were only books and the

lure of world travel called once again. In 1859 he was off to New Zealand

studying geological and mining opportunities only to return to England by 1862

and represent various mining interests. Unable to settle he returned to

Canada to become chief engineer of a large Nova Scotia coal mine to build two

railway systems in the province. It was during one of his frequent arduous field

explorations that he suffered a near fatal gunshot wound. Maybe now was the time

to slow down a bit!

The magic of telegraphy, however, never left him and in 1879

Gisborne was hired by the Dominion Government Telegraph and Signal Service to serve as

a district superintendent. His adventures in this position, while personally

inspecting the lines across Canada, are another story in themselves. For the

next 13 years, besides fulfilling his normal duties, Gisborne was in demand

lecturing at universities and continuing to patent telegraph, telephone and

electric devices. Of particular interest to insulator collectors is Canadian

patent #22449. In this 1885 patent, Gisborne advanced the idea of using tubular

iron telegraph poles and cross arms. These proved to be most useful in the

treeless prairies due to problems with fires, buffalo rubbing damage and travelers

and teamsters tending to use the wooden poles for fuel. The higher initial cost

of the 16 foot poles was offset by the reduced transportation costs, since

each pole weighed only 42 pounds. By 1888, some 3,500 iron poles had been

erected with further orders placed. Only a limited number of these iron poles

have survived the world war scrap drives.

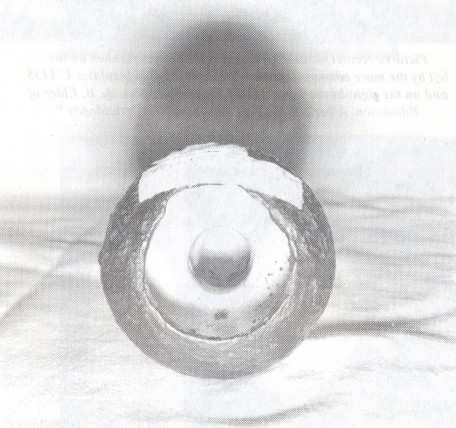

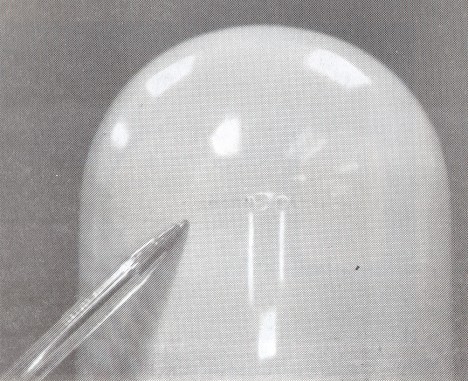

Gisborne has been involved with several insulator styles. The rare iron

insulator (pictured above and below) is owned by Mike Moon

(Manchester, MI) appears to be a Gisborne insulator based on reference material

from an electrical and Civil engineers review of Gisborne's work dated 1888.

These insulators were used extensively in Prince Edward Island around 1852.

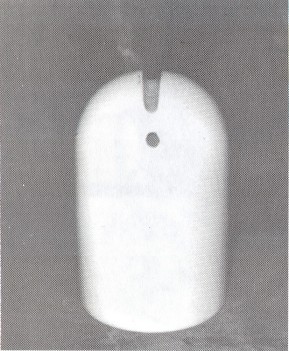

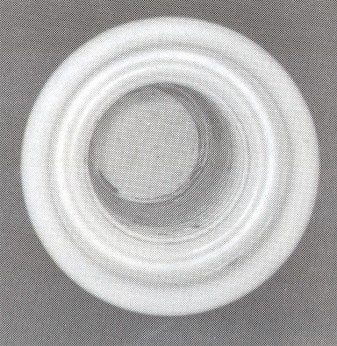

Another rare Gisborne insulator that has not been assigned a U-number , is a

large white porcelain insulator which Jack Tod called the "Gisborne

Granddaddy". It is 4-5/8 " wide and 7-1/4" tall with an inner

petticoat and takes a 2-1/2" pin. This insulator has an incuse marking of

small black letters reading "Gisborne Pattern" along the dome side.

Considering the size of the saddle wire groove, the insulator clearly is

oversized for a mere telegraph wire. However, it has been reported that years

ago, a few surviving Indians recounted that these insulators were used along the

lines where they crossed rivers. Thus, Gisborne may have seen a need for a far

heavier duty insulator for such an application of long spans.

A view of the underside and pinhole of the iron insulator.

Pictured (center) is the "Granddaddy Gisborne" flanked on the

left

by the more common, smaller Gisborne Pattern insulator U-1135

and on the right

by the large U-981 Flint Elliott Hat. L. B. Elder of

Edmonton, Alberta is the

proud owner of the "granddaddy."

Turning the "Granddaddy Gisborne" a few degrees

clearly shows the

"hole-through" in its dome.

A view of the top of the dome shows the

wire groove and the hole-through

design.

Another comparison photo depicts the size

of the pinhole of the

"Granddaddy Gisborne".

A 2-1/2 inch pin could be accommodated by the pinhole.

The incuse embossing on the side of/he insulator reads:

GISBORNE PATTERN

The common U-1135 white porcelain insulator has an incuse marking above the

wire groove in three different styles; one is the same as the

"Granddaddy"

GISBORNE PATTERN

Another is also a one line marking with the

"G" and "P" being twice the size of the previous block

letters:

" GISBORNE

PATTERN".

The third variety has the word "Gisborne" over the word

"Pattern" with the letters being large block letters of about double

the smaller size:

GISBORNE

PATTERN

The "Dwight Story" in the January, 1989 issue of Crown Jewels

connected the similarities of the CD 143, Style 2, "Dwight/Pattern"

insulator and the U-1135. It is my belief that Mr. Dwight liked the basic style

of the Gisborne insulator and copied it for his own applications in the early

1900's. The U-1136 and U-1137 are very similar in overall style to the U-1135

and retain the same characteristics "Gisborne" base indentation. The U-1135's are usually found in either white or off-white underglaze color tones.

Unincised varieties are also found as above plus a scarce chocolate brown

underglaze.

|

|

|

| Permission granted by author for use of drawings to illustrate story. |

Early collectors of these Canadian porcelain insulators had decided that they

were likely made by Bullers in England, based on company catalog information.

While I won't dispute this, I don't understand why it wouldn't have made more

sense to have them manufactured at his choice of any of the several porcelain

plants in North America. Canadian Pacific purchased 250,000 "Gisborne"

insulators by 1888 at a cost of 7 cents each. This compares with a Canadian

Pacific cost of 5 cents each for comparable glass insulators of the period.

Gisborne's insulators can still be seen in use along the C.P. lines, albeit in

fewer quantities, as the lines come down. Their availability in the future is

limited.

Mr. Gisborne belonged to a unique group of men to whom difficulties in

connection with a project added to its fascination and inspires as to its

achievement. In 1892, despite failing health and against doctor's orders, Mr.

Gisborne, feeling duty bound, undertook an inspection of the east coast

telegraph lines. He died shortly thereafter, giving of himself to the telegraph

that he revered.

|